Hawai‘i’s Soul Is at Risk

Housing prices are up, trust is down, culture and heritage feel threatened, and Lahaina broke our hearts. With record numbers leaving the state, what can we do to bring back our soul?

ONCE,

not long ago, what made Hawai‘i special were stories, songs, an impromptu hula, but especially compassion and unity. Our Hawai‘i soul was a source of pride and made us stronger. But then life took a turn.

It’s never a good sign when your big shocks are proper nouns: Rail, Maunakea, Kealohas, Red Hill. And then Lahaina. After so many violations of our land, water and trust, and the misdirection of financial resources into a rail system to nowhere, nothing feels the same. Soul is about belief in the goodness in others and ourselves; given the above, no wonder ours has frayed.

Today, “I think everyone recognizes that things are dire,” says activist-scholar-author Jon Osorio. “They are not getting better by themselves.”

“So much stuff for worry about,” agrees author, playwright and “Pidgin Guerilla” Lee Tonouchi. “Poison, no nuff water, wildfires and hurricane. An’den I worry about stuff like if local culture stay fading away too. But I tink most of my worries stay centered around my childrens.”

“Ua mau ke ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono” is Hawai‘i’s motto—the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness—but, says Lea Hong, executive director of the Trust for Public Land, “if we’re not vigilant, we risk losing Hawai‘i’s soul.”

Hawai‘i’s sense of place is disappearing under subdivisions, concrete and invasive grasses. “The threats of land loss are pressing and significant,” Hong says, “through repeated boom-bust cycles of speculation and development, lax and poorly enforced laws that allow the cutting up and conversion of agricultural lands via ‘condominiumization’ or subdivision, insufficient investment in our water systems and agricultural infrastructure.”

This is not just about the number of acres, Hong says. “It’s about connections to our history, our ‘ohana, Native Hawaiian culture, connection to place and traditions, and our ability to return to being the productive, resilient, ‘āina momona communities we once were—with aloha and pilina (connection).”

If there’s anyone who thinks we’re crying wolf, this is what loss of soul looks like: For seven years, more people have been leaving the state than moving here. They’re responding to house prices hitting a million dollars, 146% above the national average, and the highest cost of living in the nation, at 84% above. And wages too: More than half of us earn far below the federal low-income level of $67,500 in 2019. In fact, that number feels like a cruel joke to most (I’d have been low-income for the past decade and a half if I hadn’t married another writer).

Most tellingly, the share of Native Hawaiians living in Hawai‘i fell from 55% in the 2010 census to 46.7% in 2020, marking the first time that more Hawaiians lived on the continent than in the Islands. Although the majority (14.6%) end up in California, all everyone talks about is Las Vegas (3.9%).

When Vegas is acclaimed as a legitimate substitute for Hawai‘i, you know a reset is in order. Unlike people from previous generations, who might’ve worked on the continent while saving to return home, members of this new diaspora are unlikely to come back, except as visitors.

At home, it’s old news that the environment is convulsing from abuse, overuse, pollution, too many tourists and cars. Ditto for not enough community, trust, aloha. Yes, we’re on our phones too much. Yes, we get too excited about a third Chick-fil-A opening while skipping over local grass-fed beef in the store. We’re worn down by long hours and commutes. We’re sleepwalking over a cliff.

Psychologists have a phrase for it: learned helplessness. It’s ingrained from living in a place where in session after legislative session, meeting after county council meeting, outcomes are designed to emphasize our powerlessness.

But then came Lahaina. That one tragic night, and the weeks after, have felt like an encapsulation or culmination of the past few years of pandemic chaos and governmental failure. In Lahaina, we finally broke through, furiously rallying as a people.

In Lahaina, we lost one of a handful of places that still had the power to remind us of who we once were. After Lahaina, thoughts immediately turned to what’s next? Hanalei, Chinatown, Hanapēpē, Wai‘anae, parts of Kailua, Hilo, Kaimukī? We’re down to fragments. And fragmented ecosystems are vulnerable.

At the moment, the mood is shocked awake. Maui Strong. Hallelujah, our soul is back. But before the bureaucratic dumb show of delay, obfuscation and “going through channels” wears us down again, many seem ready to use this clarity, to put it and ourselves to work rediscovering Hawai‘i’s soul, renewing our relationship to it, and committing to sustaining it.

“What draws this group together is the trouble we are in, its severity.”

— Jon Osorio

Finding ‘Aelike

I have to confess, when talking to Jon Osorio, this stopped me. Dire? I know him as an uncompromising Native Hawaiian activist and university scholar. His book Dismembering Lāhui is the definitive text on the legal machinations from the Great Māhele to the events leading to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom that enabled the outright theft of the Islands by foreigners. It wasn’t what he said. It was the company he said it in.

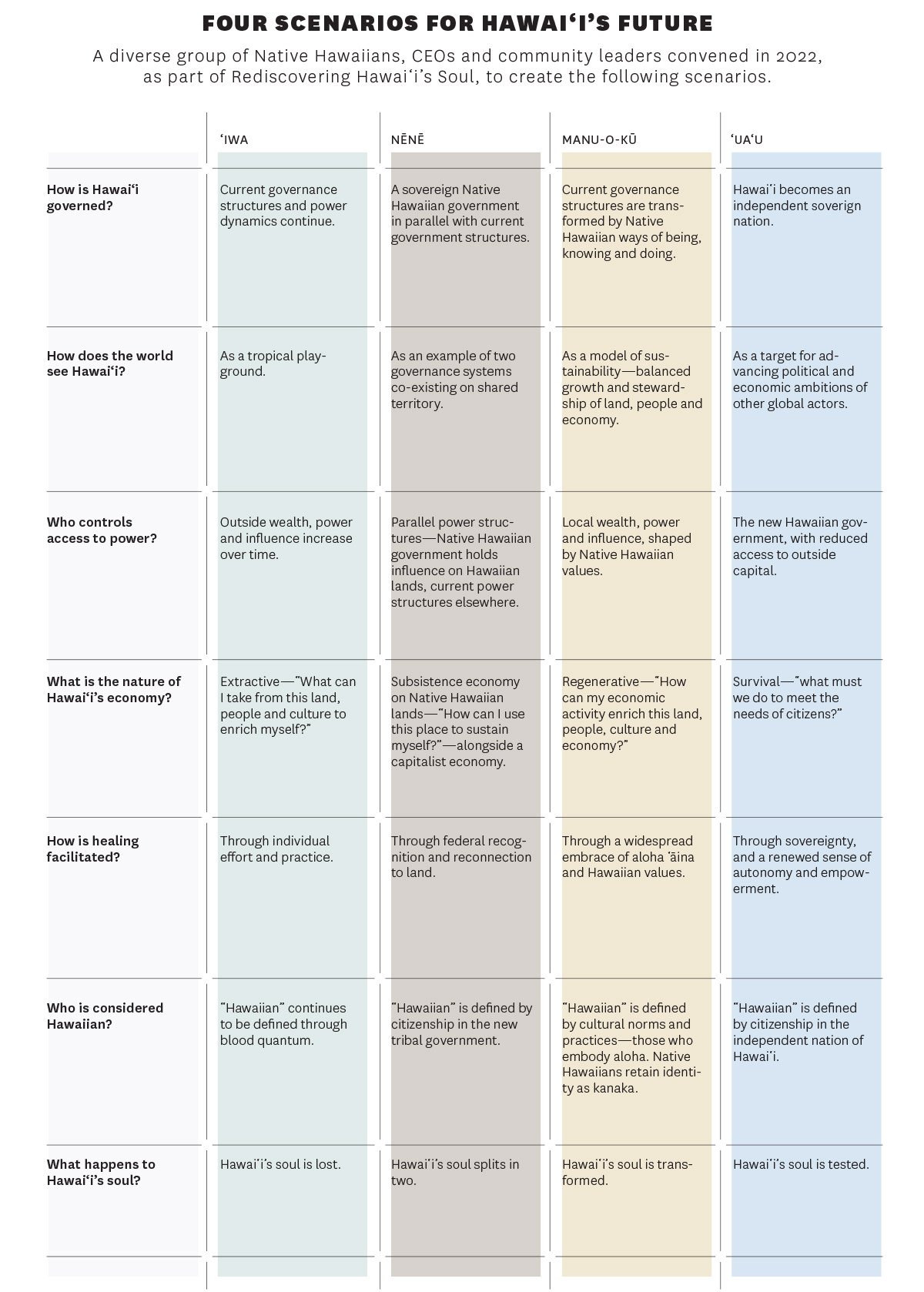

Unbeknownst to most of us, in August and September 2022, as part of a roundtable organized by the Hawai‘i Executive Collaborative, Osorio and 42 others were invited to talk about Rediscovering Hawai‘i’s Soul. Native Hawaiian activists, bank CEOs, union leaders, community organizers came together for a contentious but ultimately productive two-day affair. “It became this effort to create a sense of ‘aelike, agreement, among all of these different kinds of people,” Osorio says.

Over the next year, guided by conflict mediators who’d done the same process work in South Africa, Australia and India, some of the most bitterly opposed people in Hawai‘i met again and again, mostly in small groups. “It was about difficult things, like blood quantum, Maunakea, ceded lands, sovereignty. What we saw is that people could talk about these subjects with dignity,” says Duane Kurisu, who spearheaded the Rediscovering Hawai‘i’s Soul movement. (He is also chairman of aio, which owns this magazine.)

I ask Osorio what might come of this. Another Con Con? The constitutional convention of 1978 produced term limits for the Legislature, created the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, adopted Hawaiian as a state language and issued a proclamation calling for the end of the bombing of Kaho‘olawe. A legislative mandate for change?

“I hope that’s where we’re moving eventually,” Osorio says. “We all understand the difficulty of talking across movements, especially for kānaka maoli and people like me who are very much rooted in sovereignty and ‘āina mālama Hawai‘i, the restoration of the dignity of our culture, the ‘āina—our land—and the political ability to take care of it, minister to it, to mālama it, to have authority over it. These are things that we have fought for and struggled for our entire life. And in many ways, the people we were struggling with were some of the people in the room.”

There were fraught discussions, then a realization set in. “What draws this group together is the trouble we are in, its severity,” Osorio says. “The people who represented First Hawaiian Bank, Hawaiian Airlines, all the others, when we were in the room together, we looked around at each other and realized that we have to treat this as a coalition of thinkers. Because we are all aware that there is no political change possible unless there are substantial numbers of people behind it, which would include influential people, and many different houses of society, basically agreeing on what we can do.”

Ho‘omau ka hana. The work continues.

Compassionate Action

But we don’t have to wait. There’s Chinatown. On the cusp of its biggest revival, it’s our best-preserved architectural district—and also perennially threatened. We’ve seen revivals, but this time the change feels real. Soul is a big part why.

It’s no secret that Chinatown’s biggest problems are homelessness and drugs. It may seem the opposite of compassionate that, after protracted negotiations with the city, the River of Life ministry transitioned out of the neighborhood in April 2022 despite its initial resistance. The results were validated by its success. After starting a mobile meal delivery system with 78 trucks stopping at locations across O‘ahu, the group has since brought 95 people off the streets, compared with 15 the previous year, Rann Watamull, River of Life’s president, says.

Gregory Dunn, president and CEO of the Hawai‘i Theatre Center, appreciates the way the homelessness problem has been handled by Mayor Rick Blangiardi and his staff. “Working to improve the lives of all of Chinatown’s residents (both housed and unhoused) is what the neighborhood needed to see happen first. … It’s helped us turn the corner,” he says.

That corner feels calmer every day. We celebrated my wife’s birthday at one of Fête’s outdoor tables on Hotel Street the other night—and lived to tell about it. Between bites of J. Ludovico chicken, we imagined what could be if café tables lined the mauka sidewalk all the way from Fort to River streets. Why couldn’t there be more outdoor seating in the River and Fort street malls, the way they do it in Paris? Going further, why not envision a couple of performance spaces, underwritten by the city and state? There could be nightly walk-in shows with improv, comedy and sketch theater. And while we’re at it, let’s tax hotels to fund an entertainment district for us. (And will someone please write a very local musical that can run for years and years?)

Right now, Chinatown can use our attention and our help, which boils down to our dollars. Call it soulful spending, if you like. More than a dozen new restaurants, boutiques, bookstores and shops have opened in the neighborhood. Hawai‘i Theatre has been energetic and inclusive. We attended a recent concert featuring the Hawai‘i Symphony Orchestra performing with the Honolulu Jazz Quartet, with a special appearance by Keola Beamer. The hall was packed, the crowd enthusiastic; it felt like family.

Lahaina was a place encrusted with layers of memories and meaning for a wide variety of people; its raffishness was part of its charm. Even more historically intact, Chinatown has that same funk that you just can’t get from Disney imagineers. Urban planners on the mainland and in Europe would love to have a Chinatown—we should treasure it, and mālama and support its brave new iteration.

“The whole point is not just to move money to farmers but to build community around farmers.”

— Mary Spadaro

‘Āina Action

The food on our plate at Fête was largely sourced from the North Shore, proof that the elements that stir and sustain life are here. But as Hong, from the Trust for Public Land, points out, we’re losing land just as it becomes starkly clear, with the wildfire in Lahaina, that the ‘āina should be in production, not just on Maui, but everywhere. Without green fields and taro lo‘i and fishponds, the entire island chain is a firetrap, in perpetual drought.

To also ignore the consequences of importing 90% of our food is foolhardy and asking for disaster. A hurricane, pandemic, work stoppage or outbreak of hostilities could cut us off like that. We only have the resources to survive a week before serious shortages, 14 days before actual deprivation. Without the basics of survival, even landlocked societies quickly unravel. On an island as isolated as ours, the scenario is positively dystopic.

As it happened, I’d been reading an unpublished monograph by Mark Panek about how O‘ahu was once the “breadbasket of the Pacific,” before sugar cane plantations took over agriculture. Back then, we were meeting all of our food needs and exporting shiploads of fresh produce, pork and poultry to San Francisco and Seattle. So we can’t say it hasn’t been tried.

And it’s happening now. For 45 years, the Trust for Public Land has been quietly leading the restoration of our food sovereignty. TPL prefers to work under the radar, but Hong spreads praise widely, mentioning current partners Ho‘okua‘āina, Kauluakalana, Aloha ‘Āina Health Center, Maunalua Fishpond Heritage Center (Kānewai Spring), MA‘O Organic Farms, Ka‘ala Cultural Learning Center, Waipā Foundation, and Ho‘āla ‘Āina Kūpono. TPL also works with Paepae O He‘eia and Kāko‘o ‘Ōiwi from time to time.

How can we the people get into the act, in addition to joining TPL and contributing? Hong and TPL’s Aloha ‘Āina director Reyna Ramolete suggested I talk to Mary Spadaro of Slow Money Hawai‘i, which helps individuals make small loans to farmers and producers. Having retired as a nonprofit development executive, Spadaro says she got “frustrated waiting for people to make policies that make sense. I made up my mind to just do it,” after attending a North Shore food summit.

That J. Ludovico chicken on your favorite restaurant’s menu comes thanks to Slow Money and Spadaro, who introduced Ludovico to his first lender, an older farmer named Milton Agader. Spadaro still fondly recalls what Ludovico said later: “For me, the most valuable part was not the money, although I needed it, but the relationship I developed with Milton,” whose Twin Bridge Farms on the North Shore supplies Hawai‘i with asparagus.

Probably the most soulful thing about Slow Money, says Spadaro, is that “borrowers and lenders are required to become acquainted. The whole point is not just to move money to farmers but to build community around farmers, so people have a better understanding of who grows their food, and to have better relationships with their food.”

Slow Money only works with farmers who employ sustainable or regenerative methods of farming. So far, it has assisted in 68 loans and has acted as a trustee for about 50 transactions through a microfinance funder.

Organizations like TPL, Surfrider and the Sierra Club fight never-ending battles with developers and politicians who frequently co-opt buzzwords like “affordable and sustainable.” But sometimes, individuals appear out of nowhere to make their own daring interventions.

That’s the case with Patricia Godfrey, who showed up at a tax auction, bought a priceless piece of O‘ahu’s watershed that had been foreclosed upon, then turned around and gave it to the state. She requested no fanfare or press.

Later, in a local journal, she wrote: “I did it so that the native Achatinella Fuscobasis, a tiny striped snail found only in Pia Valley, can survive. I did it for the O‘ahu ‘elepaio, Chasiempis Sandwichensis Ibidis, a small, endangered songbird whose only home is within Pia and the surrounding Ko‘olau valleys, and for the Asplenium dielectum fern, found only in Pia. … I did it to lock in place a piece of the Ko‘olau Watershed. Pia, a sharply inclined valley to the east of Honolulu, gathers and filters rainwater and is a source of our drinking water, a source of our life. The life of the snail, the bird and the fern and our human lives are entwined.”

“They stole Kaka‘ako right under our noses.”

— Luciano Minerbi

Hale Action

Affordable housing has been the most pressing need, especially in Honolulu, for the past four decades. It’s our greatest failure, because from it stem so many troubles, including high rents and real estate prices that cause so many families to crowd together. (We are the state with the highest number of “extreme multifamily” housing situations.) So many others are forced out of the state or into the street.

We could have righted the ship in the ’60s, says William Chapman, dean of the University of Hawai‘i School of Architecture. “But we blew it. Honolulu has these charming apartments from the period, but they’re predominantly two-story. If we’d not built all these single-family home tracts and instead built apartments that were three stories tall, there would be no housing shortage. And no sprawl.”

In the 1970s, state planners jumped on the urban redevelopment bandwagon that was wiping out poor and minority neighborhoods on the continent to make way for gentrification. When Mayor Frank Fasi resisted such plans for small-business district Kaka‘ako in 1976, the state, under Gov. George Ariyoshi, and Legislature created a development entity that, after many false starts, forced out the hundreds of businesses there and imposed a corporate regime under mainland monolith General Growth, which later sold the troubled development to Howard Hughes.

“They stole Kaka‘ako right under our noses,” says Luciano Minerbi, professor emeritus of urban planning at UH, who developed copious studies and proposals for urban Honolulu with his graduate students starting in the early ’70s. “Everything we advised, they did the opposite.”

First, affordable housing was never in the original plan, which called for two dozen luxury condo towers, marketed to the offshore buyer market (with local CEOs and finance executives picking off choice units for themselves). Complaints and protests resulted in developers throwing in a sop to those being displaced—at first, a developer would just make a token payment to the general state fund, which later became a few units in a building outside Kaka‘ako to be built later. Pressure finally forced developers to create “affordable” units in the same towers that the luxury buyers lived in, though at least one came without front-door privileges.

Even when a quarter of a building was set aside as affordable, in return for hefty city subsidies, it was all a big shibai. Given Honolulu’s depressed salaries, the $144,000 ceiling for median qualifying income enabled the well-off to snatch them from the mortgage- and liquidity-challenged classes for whom they were ostensibly intended.

This history is important, because it predicts down to the inevitable zoning variances allowed (buildings up to 450 feet) what will happen in our next, and last-chance, affordable housing project—the Hālawa stadium site. An enormous plum for the picking by some lucky international construction conglomerate, Hālawa is already doomed. If this project works out like past ones, we’re facing a multigenerational boondoggle that could well dwarf Skyline, as rail is now called, in both financial and aesthetic costs.

But it’s not too late to stop it, Minerbi says. First, as he suggested in his 1977 paper: “Don’t give state and county land away.” Second, no more tall towers. Third, allow small locals-only developers to compete for smaller parcels of the job.

“We are captive of a very bad system,” he says. “It’s a machine to make money for the bigger entity, the bigger corporation, and of course, the unions. We have paid the price for it, with homelessness, our housing shortage, taxes.”

In multiple studies, op-eds and letters over the past 46 years, Minerbi and his peers have called for human-scale designs for small apartment buildings from three to six stories (with an occasional 12-story). This is the scale of acclaimed neighborhoods of great urban cities such as Paris, London, Barcelona, the classic parts of Manhattan. These types of buildings create community instead of alienating it, and the skyline.

Letting small local developers do the job cuts out the boondoggle boys from Wall Street and private equity. Keep the money at home, Minerbi says, by cultivating “incentives for small property owners and small developers to build this housing at a human scale and cost.”

Instead of a monolithic slab of towers squatting like Moloch on Hālawa, we can end up with a complex, diverse, not-state-planned quilt of local architecture—much of which, if you look at small apartment buildings from the ’60s, is quite charming, sited to catch the trades, usually embellished with a proud developer’s signage and Hawaiian-style touches.

It’s O‘ahu’s last chance at a big play, Hālawa. We can employ local contractors and workers for generations, keep the money at home, retain what’s left of our human-scale skyline, house the homeless and leave plenty of room for small businesses to thrive, not just the deep-pocket chains and flashy tourist restaurants.

So-called realists may say that train has left the station, but, if you know Hawai‘i, every solid plan melts into the air every 12 months or so. And the alternative is unthinkable, really.

As for the stadium, five or six Saturdays a year aren’t worth the $500 million for a structure that will dominate and deform O‘ahu’s last great open urban space available for affordable mixed-use housing. So what if the Warriors play at Ching stadium? It’s bound to make the university area more lively, once the kinks are ironed out. The local paper already puts high school stories on the front page, a small-town thing that’s full of soul.

Moving Ahead

Rediscovering Hawai‘i’s Soul may test our individual credulity and patience. But to continue down the same path seems equally incredible, as in assuring the destruction of Hawai‘i as we know it.

To Osorio, it’s the process and respect for Native Hawaiian scenarios that matters. “That’s what’s giving me hope,” he says. “The willingness of business corporate types to consider the reality and the plausibility of a restoration of Hawaiian independence, of an independent Hawai‘i, or to consider the value of a government in Hawai‘i that is distinctly separate from the rest of the United States and really was going its own way, driven by Hawaiian cultural values—the fact that they’re willing to consider it, those corporate types, when matched with kānaka maoli who have been struggling against these organizations all their adult lives, that either side would consider the possibility of entering into a political progress with those people, and building something vital—that’s actually the miracle of this process.

“That’s what I’m seeing and that’s what’s giving me hope.”