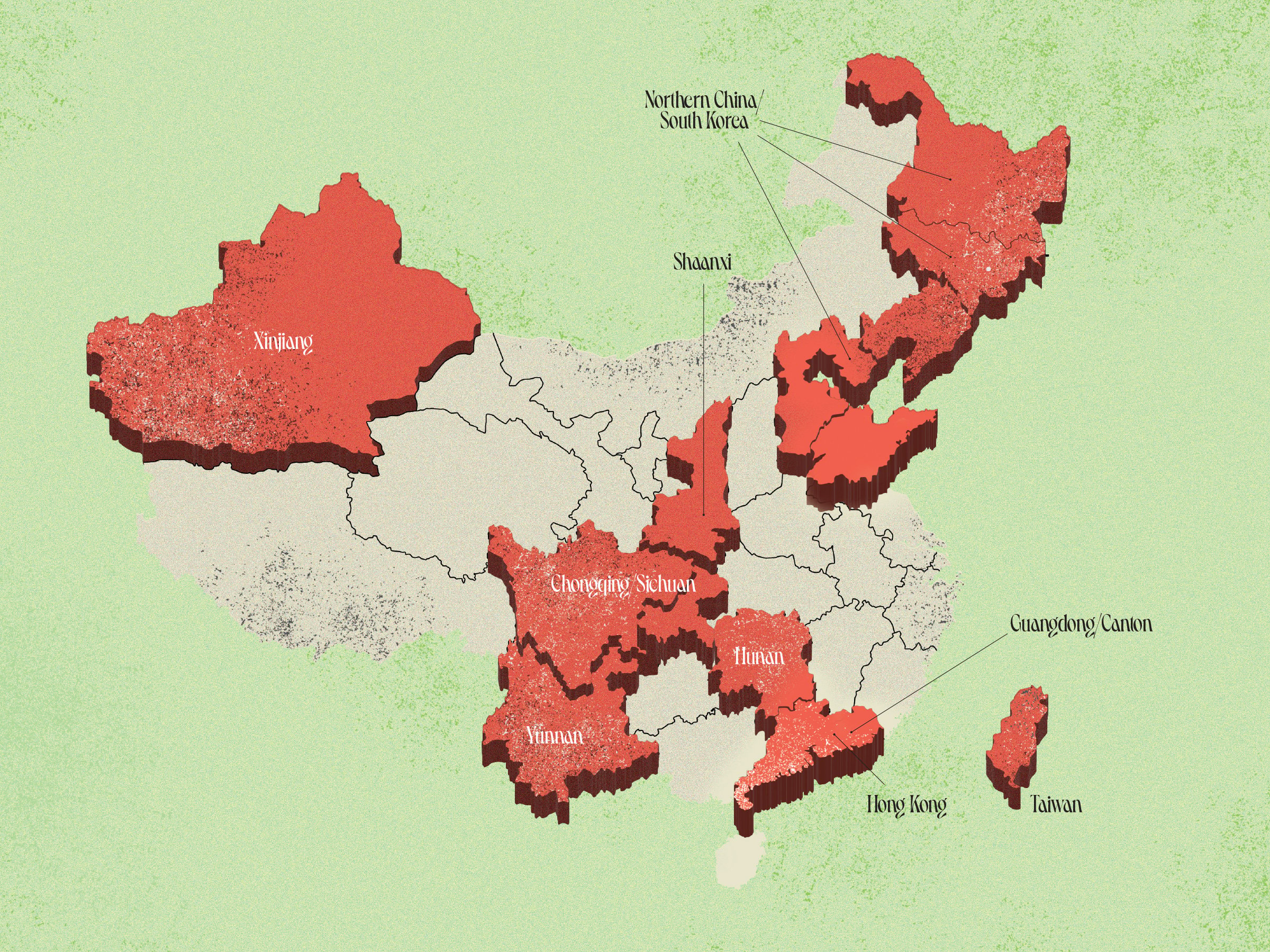

never been a more exciting time for Chinese food in Honolulu. No longer are we bound to orange chicken and cake noodle—though never ask us to give them up! A window into China’s immense regional culinary diversity has been cracked, bringing in the hot and numbing spices of Sichuan, the skewers of northern China, the thin rice noodles of Yunnan. It reflects a diversity unfolding across the country: Whereas the first Chinese immigrants came to the U.S. primarily from the southern province of Guangdong, newer waves have arrived from Fujian and other regions.

The result is a heady mix of different culinary styles at eateries around the city—from the tiny, family-run Wu Wei Chong Qing to Los Angeles import Chengdu Taste to large chains like Meet Fresh, which draws on Taiwanese traditions. Even longtime restaurateurs have adjusted to the changing demographics.

When former owner Kevin Li opened King Restaurant and Bar in 2019, he sensed a shift in tastes and departed from the localized Chinese food he served at his previous restaurant, the homey neighborhood spot Hung Won. Instead, he offered Sichuan dishes like mouthwatering chicken alongside honey walnut shrimp and salted egg yolk crab.

King Restaurant’s repositioning is a larger trend writ small: It’s not a coincidence that the rise in diversity comes as Chinatowns across the country are struggling. Some of our longstanding Cantonese-style eateries, both inside and outside of Chinatown—Nam Fong, Golden Palace, Tasty Chop Suey—are closing as the older generation calls it quits, giving way to newer restaurants with their regional specificities.

And so, yes, as diners we have so many more choices and, especially in Hawai‘i, an appreciation for both the familiar and novel, so that ultimately our dining scene is like the best Chinese banquet: wonderfully textured and complex and perfectly in balance. —MC