2026 Private School Guide Feature: Outstanding Teachers

We spoke with three veteran private school educators who have made significant contributions to their schools.

The importance of teachers can’t be overstated. They are the backbone of education, and when students consider their most consequential connections at school, they often cite teachers who inspire and support them.

This year’s Private School Guide features three long-standing teachers who have made significant contributions to their schools over the past 10 years or more. We asked administrators to each name a veteran teacher with exceptional teaching practices who positively impacts student learning by building strong relationships, exemplifies school values and positively influences campus culture with their passion and dedication.

The educators they selected all meet the criteria and more. Here’s what makes each of them stand out.

Loren Otake

The Rock

Veteran teacher Loren Otake, who has multiple roles at Pacific Buddhist Academy, says his reward is seeing students mature into young adults.

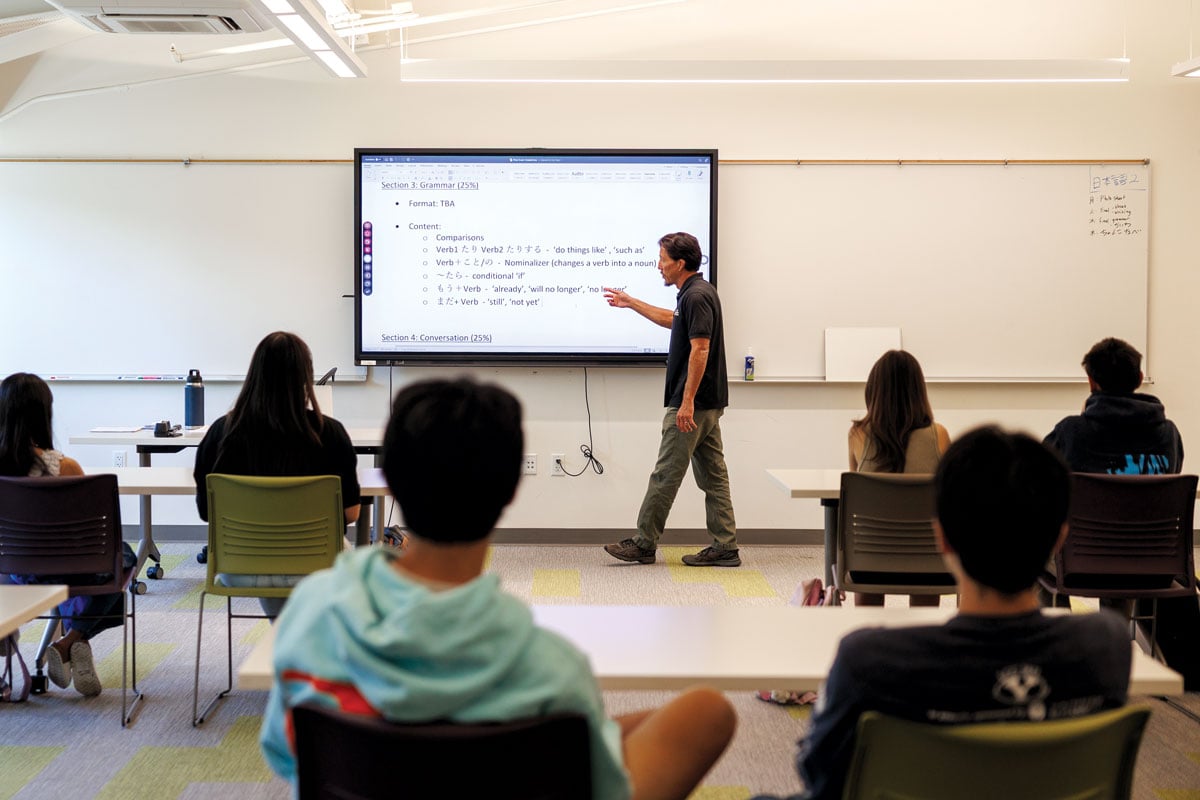

After 17 years at Pacific Buddhist Academy, Loren Otake is considered a “rock,” an educator whose steadfast presence spans well beyond the classroom. What makes him particularly beloved at the Nu‘uanu school is his straightforward, relaxed way of relating to students. There’s no pretense, just a sincere desire and commitment to help students achieve academically, gain valuable experiences and be good to others, which are all critical to him.

Otake’s primary role is to teach Japanese, but he also directs the study abroad program, leads the advisory program, coaches the grapplers club and golf team, and recently assumed a new role as athletic director. In addition, he coordinates the high school’s Sōran Bushi, a traditional Japanese folk dance, at the academy’s annual Taiko Festival, and spearheads the newest sports club, Nā Mo‘o O Ke Kai, for students interested in shortboarding, longboarding and bodyboarding.

“I really respect his knowledge about the ocean. It doesn’t matter if you’re a new or experienced surfer, he always has the right advice to help push you to the next level,” says Liam Antipala, a senior and Nā Mo‘o O Ke Kai participant.

Says Megan Lee, the school’s director of advancement: “He embodies the heart and spirit of Pacific Buddhist Academy’s mission. Whether it’s in the classroom teaching Japanese or taking students out in the water during a swell, he displays enthusiasm, resilience and a deep commitment to education.”

“Sensei Otake,” as he’s called at school, shrugs off the accolades, saying everything he does aligns with his personal experiences and interests. He’s a longtime surfer, he explains, and a former wrestler and wrestling coach. He’s also lived in Japan, making him a good fit to head up the school’s Ryukoku Sogo Gakuen cultural exchange program.

“PBA is a part of an organization of Shin Buddhist high schools,” Otake says. “We’re the only school outside of Japan, so students come study abroad here, and we send our students there for a six-week program at a school in Kyoto. It’s a good learning experience.”

For the school’s advisory program, a regular, nonacademic time when students connect with teachers, Otake says he organizes activities that align with school values. This includes having “Sangha circles,” a Buddhist practice focused on the art of communication and negotiation. The school doesn’t try to convert students to become Buddhists, Otake says. Rather, Buddhist values are woven into the curriculum and code of conduct. “Our mission, our vision and student code of conduct are all based on certain Buddhist values, like selfless giving, patience and mindfulness, which are just good values in general, not necessarily religious.

“We do our best to take a nonpunitive approach to discipline and have restorative practices. It comes down to how you treat each other and how you go about redirecting student behaviors, so instead of pointing fingers and saying, ‘Who did that?’ You ask what happened. What I discovered is that by doing this, kids are a lot more honest.”

With fewer than 100 students at the Nu‘uanu campus, Otake sees the school’s small size as a plus, allowing faculty members to build strong relationships with students and their families. “To me, that’s special,” he says. “I feel passionate about making PBA the best place it can be, and my favorite thing is watching young teenagers mature and grow into young adults. That’s cool and rewarding.” —DS

Marcie Herring

Consummate Collaborator

Marcie Herring, director of college and career counseling at St. Andrew’s Schools, says her passion is to help students discover their own passions.

Marcie Herring warmly offers green tea and Royce’ Sakura chocolate after welcoming me to her classroom at St. Andrew’s Schools. A few minutes into our conversation, it’s clear why students would gravitate to her, not just for college and career counseling, but also for life mentoring.

She’s friendly and upbeat, yet soft-spoken, and more comfortable touting her students than herself. When complimented for her classroom, which is bright and colorful with a clean, minimalist aesthetic, she proudly says it was designed by a former student, an aspiring interior designer who wanted to create a calm space where people could be creative. “The beauty of it was that when students came in and saw it, they immediately said, ‘It’s so peaceful,’” Herring says. “She was able to translate her vision.”

There’s a piece of artwork, a block with the word “Maximizer” painted on it. Herring says it was given to her by a former student who told her she helps students “go from good to great.”

It’s an apt characterization that aligns with her purpose—her ikigai, Herring says. As director of college and career counseling, she’s passionate about helping the Priory’s middle and high school girls discover their strengths and interests, so they can apply to the right colleges and pursue careers they love.

Before coming to St. Andrew’s in 2009, Herring had her own college and career coaching business. Her first role at the school was as a social emotional counselor. She decided to take the job because she was drawn to the legacy of the school’s founder, Queen Emma Kaleleonālani, whom Herring describes as a can-do visionary. “She was empathetic to people’s needs, and then she created solutions,” Herring says. “She was concerned about education for girls, so she started St. Andrew’s as a school for girls.”

In 2013, Herring helped launch “Priory in the City,” a networking and mentoring internship class, which she still leads. She took on her current role as college and career counseling director two years ago.

“We combine college and career coaching with our internship program, which gives students the opportunity to be mentored by industry professionals,” Herring says. “We work with students over time, so we get to know their passions. I love listening to what they’re interested in, then helping curate experiences that might be of interest to them.”

With Priory in the City, students get real-world experience, interning with architects, CEOs, doctors, artists and others. Herring says the program has lots of success stories. She cites a former student who, while at St. Andrew’s, interned at UH’s cancer center, working with a doctor trying to find a cure for cancer. “That led her to continue her science pathway and she’s now studying at Johns Hopkins University, continuing the work,” Herring says. “It really makes a difference to start early.”

Sometimes, the internships students land are exactly what they hope to do in their careers; other times, it’s not a good fit. Yet both outcomes are valuable, she says.

“The personal and individualized attention that each student is able to receive from Marcie makes their journey to college a unique and invaluable experience,” says Ruth Fletcher, president and head of school at St. Andrew’s Schools. “Marcie guides each student with care and compassion, while also setting a high standard for striving to be their personal best. … She is the consummate collaborator and a gracious presence every day, both inside and outside the classroom.” —DS

Heidi McGivern

The “Go-To” Teacher for Technology

A 35-year veteran at Maryknoll School, Heidi McGivern leads the way in tech instruction while cultivating trusting relationships with her students.

Students in Heidi McGivern’s senior English class call out pros and cons of artificial intelligence as she walks between desks, listening, responding and nudging them to dig deeper. “Facial recognition keeps your identity safer,” she tells them. “It can help track down criminals. Is that beneficial for our society today? How?” She then offers tips for finding credible sources on educational and academic databases.

It’s just one example of how the longtime Maryknoll teacher interacts with students, encouraging them not just to acquire academic knowledge, but to connect with what they’re learning. She also asks about their sports, hula practice, what they’re reading, how they’re doing. The night before she’d attended a senior night event.

“One of the big reasons why I’m still teaching today is the relationships, because I can see progress being made through relationships,” McGivern says. Now in her 35th year at Maryknoll, she’s become the “go-to” technology teacher. “Sixty years old—how’s that?” she says, grinning. “Somebody has a tech problem, they come to me.”

Maryknoll president and head of school Shana Tong praises McGivern for always putting students first and providing each student with individualized attention. The two have worked together for decades. In 2002, McGivern won the Hawai‘i State Middle School Teacher of the Year award and in the same year earned a master’s degree from UH Mānoa. In 2011, she won a National Teacher of the Future award from the National Association of Independent Schools.

“I’ve always admired how she is able to pivot with new programs, new instructional strategies,” Tong says, especially on technology. “She just kind of led the way, and she explores and makes it fun and wants to share her knowledge with her colleagues and her students.”

McGivern points to growing up on a 400-acre dairy farm in Washington state with six siblings for her “let’s try it another way” approach. With such a large family, she learned the importance of adapting whatever resources were available to tackle challenges. She met her husband, Jeffery, who’s from Hawai‘i, at St. Martin’s College, prompting their move to O‘ahu where they raised three children.

Back in class, McGivern has teams of students competing in a fast-paced game to identify literary terms. They then move into debate prep before winding up the class with a segment dubbed a “brain break.” Students reach for a variety of books to help them navigate life. The books include Grit, Mindfulness. Mindset, Who Moved My Cheese? They read quietly then discuss what resonates. One teen explains how he struggles with reading long passages. She suggests he download an audio version of the book before the next class: “Bring your earbuds, and you can listen to your soft skills book if that’s the way you learn better,” she tells him.

Even during her spare time, McGivern shows her zeal for learning. She works summers at nearby Punahou School, teaching coding and game design to sixth graders in a program for public school students.

“She just has this knack for bringing people together,” Tong says. —RD