Lights Out? Hawai‘i’s Energy Future Looks Dire

Without swift action, Hawai‘i faces more exorbitant electricity costs. What will it take to move aggressively enough with renewable alternatives?

In the front yard of Stacey Alapai’s home in rural Makawao, two salvaged solar panels are set up on the grass. They’re charging a battery generator, which powers her refrigerator and other appliances. The setup is basic—Alapai plans to eventually move the panels to her chicken coop roof—but she hopes it serves as a grassroots model to help other working-class Maui families access renewable energy.

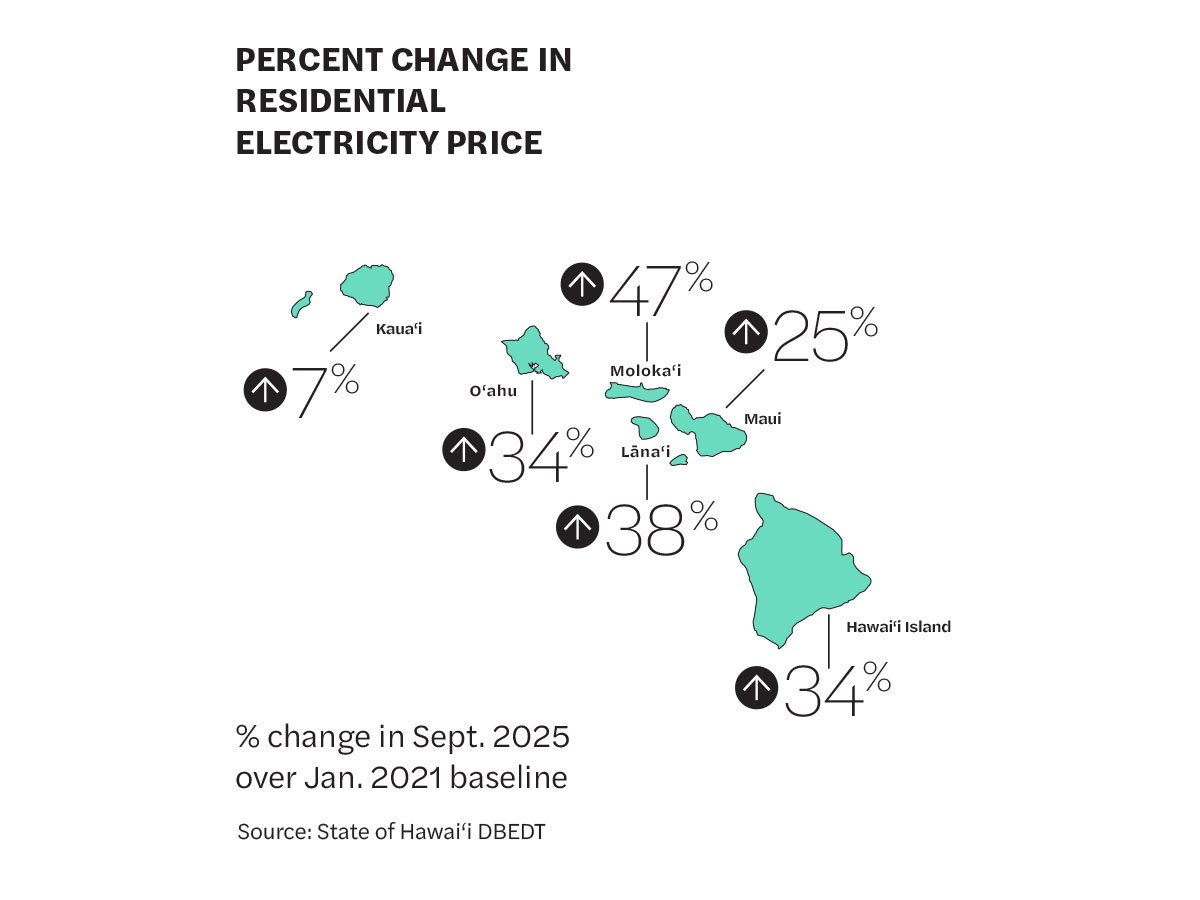

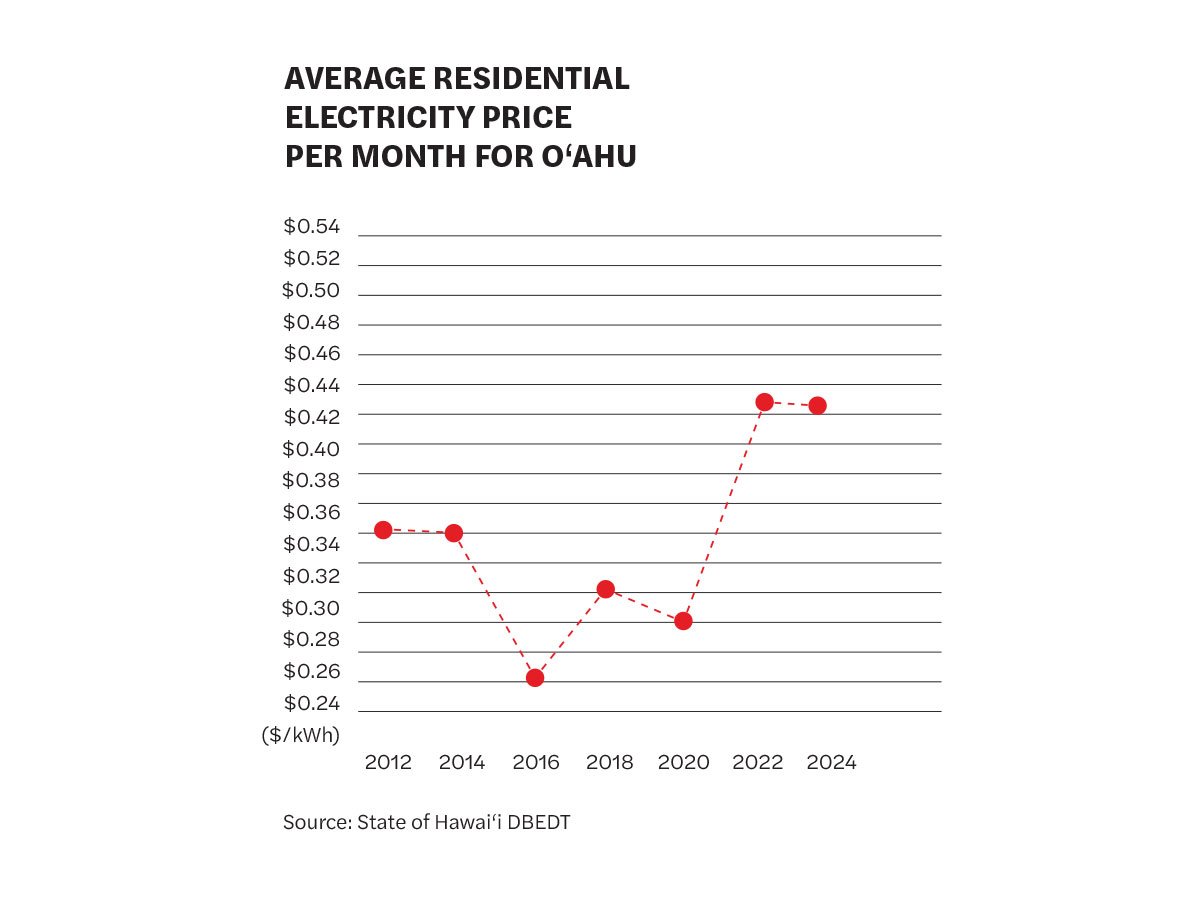

Alapai’s pilot program aims to supply households with battery generators and used solar panels, an effort fueled by concerns about her own electric bill and her quest to figure out why it was rising. In her case, the culprit turned out to be a faulty water heater. But along the way, she asked other questions. Why is power so expensive in the Islands, with bills two to three times higher than the national average? And is Hawai‘i moving quickly enough to achieve its ambitious renewable energy goals?

“To understand what was going on required me to be persistent to get any kind of help. That was the gateway for me realizing being poor is expensive when it comes to this issue,” says Alapai, who in 2025 co-founded the Upcountry Energy Resilience Project with fellow organizer Shay Chan Hodges. The goal, she says, is to help households adopt green energy.

While Alapai’s efforts are not a cure-all for Hawai‘i’s broad energy problems, she may be building something valuable: community awareness and eagerness to explore alternative energy sources. Experts agree.

Net Zero by 2045? It Won’t Be Easy

Researchers, legislators and policymakers say weaning the state off its imported oil addiction while rapidly building to 100% net electricity generation from renewable sources, as required by state law by 2045, will impact every part of daily life and could be one of the most significant challenges Hawai‘i has ever faced.

Tomorrow’s grid will almost certainly mean new infrastructure and technologies creeping into neighborhoods statewide; it’s expected to require billions of dollars in government and private spending, and community tensions are almost inevitable. Underlying the conversation is the reality that the demand for electricity (locally and nationally) is only rising, with transportation going electric and AI technologies poised to sap more energy from the grid.

While a clear roadmap for achieving “energy sovereignty” in the Islands remains unclear, there is also a growing acknowledgment that the state will need to take aggressive action—and soon—to reach its energy goals. That’s why it’s exploring technologies beyond solar, from geothermal to biofuels and even non-renewable energy like nuclear.

Although Hawai‘i can celebrate sizable progress in renewable energy generation, the wins are dwarfed by the work ahead. “Hawai‘i is a national leader in renewable energy goals, yet we are lagging in our renewable energy transition,” says David Mulinix, co-founder of Greenpeace Hawai‘i.

Community Support Is Critical

Michael Colón, energy director for impact investment firm Ulupono Initiative, says amid the flurry of investments, community members need to be assured that costly and disruptive energy projects aren’t just extractive but will improve their quality of life—and lower their electric bills.

“The community needs to be behind it, and the community needs to benefit,” Colón says. “How do we enable communities to do their own energy planning? We have the right mindset and focus on people, and so I think those values will show up when it’s important. We also have great resources in Hawai‘i from a renewables standpoint. It’s a matter of making it all come together.”

Residents of all incomes also must start seeing dividends from renewable energy investments, agrees Kealoha Fox, the city’s chief resilience officer. “We have to find new sustainability projects that get to the heart of infrastructure upgrades and really demonstrate this is part of a broader effort to cut costs. We don’t have the luxury of simply reducing carbon emissions. It has to hit people’s pockets.”

Fox now pays Hawaiian Electric about $700 a month to power her three-bedroom home in Mililani, built in the 1970s. And that’s without air conditioning.

So, while energy efficiency efforts on government buildings help taxpayers—they lead to lower costs for the state and make it possible for officials to divert funds to other programs—she knows home power bills are where the public sticker shock is really felt.

Where Do Things Stand?

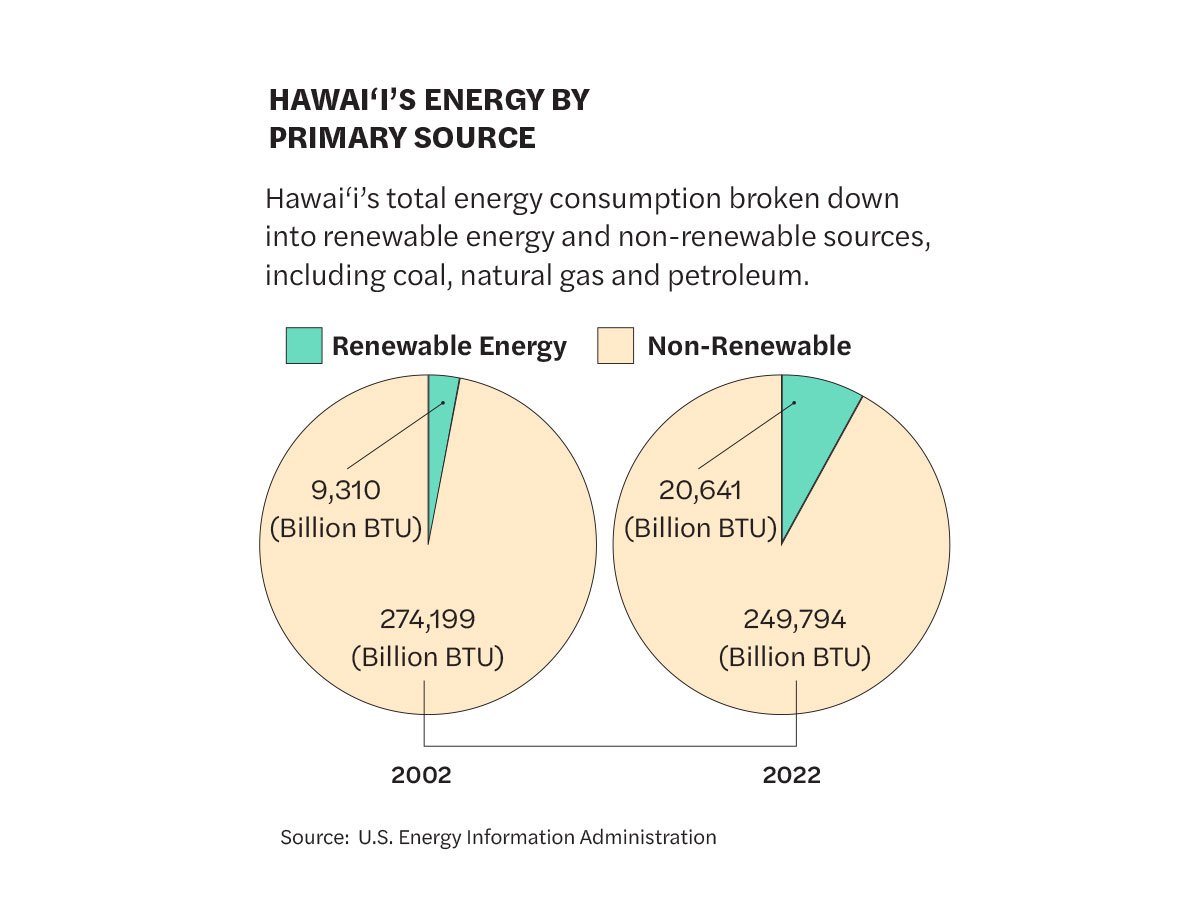

About 38% of Hawai‘i’s electric generation comes from renewables, up from about 15% in 2015, when the state’s 100% renewable energy mandate was adopted. While onlookers applaud the strides made in decarbonizing an island-by-island patchwork of grids, they’re quick to note that progress has been uneven, especially for low-income families, and that the work left to do must be achieved at a faster clip. Colón notes one significant area of concern on O‘ahu is slower-than-hoped progress on renewables.

State Sen. Glenn Wakai, chair of the Committee on Energy and Intergovernmental Affairs, says lower power bills from renewables haven’t materialized, either.

“We’ve been on the renewable energy crusade for 10 years, but our electricity rates continue to rise,” he says. And he points to issues at Hawaiian Electric, which he says is tackling its renewable energy obligations while also grappling with its response to the Maui wildfires and, more broadly, seeking to update its aging, inefficient infrastructure. “There are big issues that are going to hamper our big goals,” he says. “Hawaiian Electric is in a period of trauma, and they have to figure out how to stay alive and then they have to figure out how to keep the lights on.”

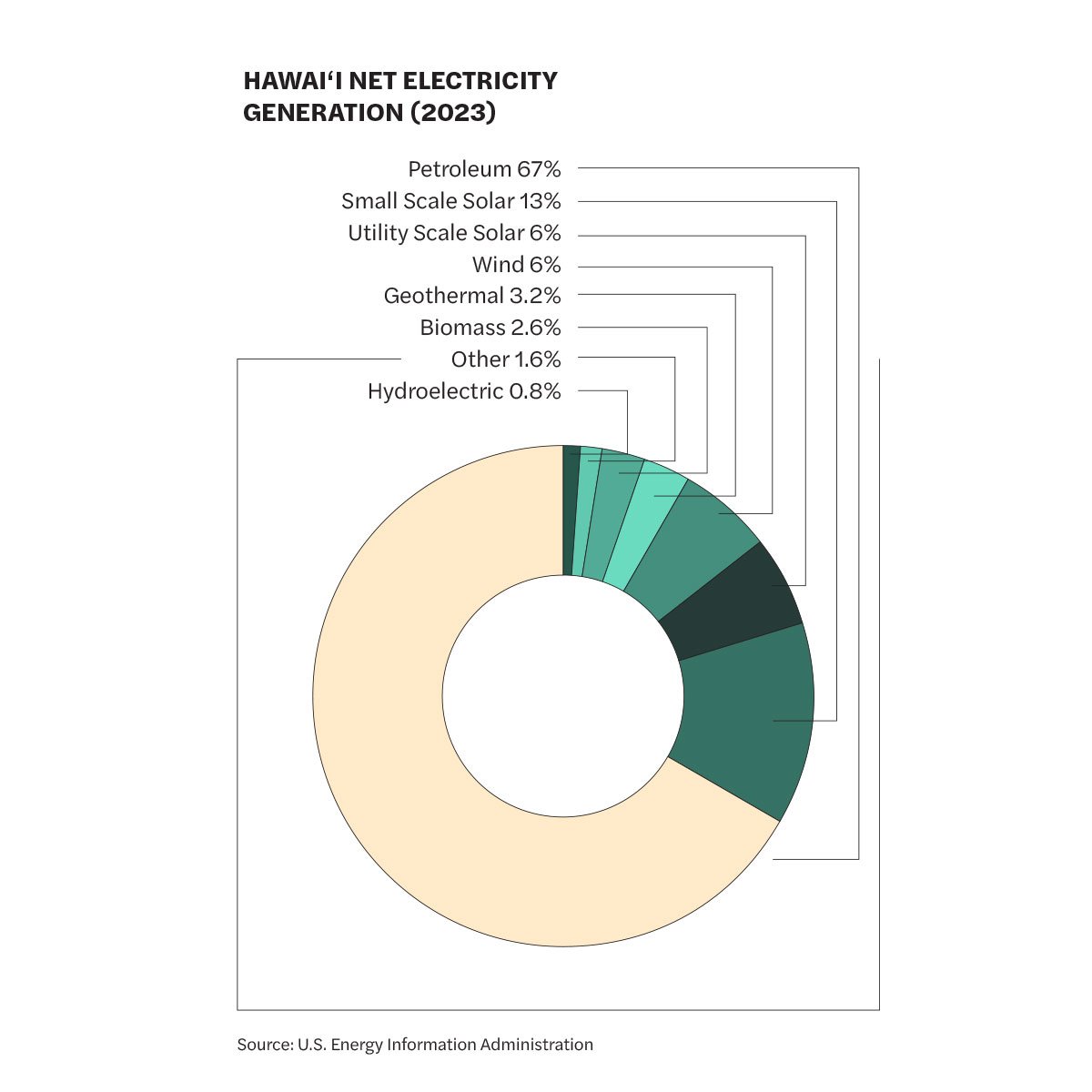

HECO officials acknowledge the scale of the undertaking—and that Hawai‘i’s pathway for achieving total renewable energy generation remains uncertain. While solar power has made up most of the state’s renewable energy gains, it’s unlikely to get the Islands to the finish line, experts say. And in the search for other top renewable energy sources, geothermal power and biofuels are emerging as top contenders.

At the same time, with energy sovereignty at the forefront, lawmakers are studying whether nuclear—hardly renewable and banned by the Hawai‘i Constitution—could be a viable option amid a global race to build cheaper and safer “small modular reactors,” or SMRs. They would be situated in communities to help keep up with rising energy needs.

The Controversy

Wakai argues Hawai‘i “needs to be part of the discussion on nuclear” and the Legislature is slated to take up the issue this year, armed with a working group report on the near-term potential for the technology in the Islands.

But he and others agree nuclear presents significant hurdles, not least of which includes a two-thirds vote in the Legislature to overturn the constitutional ban.

Community sentiment to nuclear projects is likely to be skeptical at best and hostile from several quarters, including from environmentalists. And while SMRs are getting plenty of attention globally, including from the U.S. military, none have yet been built in the United States. (The first ones in the U.S. aren’t set to come online until the early 2030s.)

Mulinix, of Greenpeace Hawai‘i, says he was “quite surprised” when he first heard legislators wanted to investigate the feasibility of using nuclear power in the Islands. “The fact that nuclear power is not safe, clean, cheap, nor efficient is settled science,” he says. “Regulators have searched for over 70 years for a permanent disposal site and still have found no safe place in the entire country to store nuclear waste. Nuclear waste we create in Hawai‘i would be stuck here.”

He adds that it would hardly be considered green to ship radioactive waste out of state. “And why would we want to burden and pollute someone else’s home with our radioactive waste for thousands of years? That is not pono.”

The State Committed to Lower Energy Costs

Gov. Josh Green, meanwhile, says that while his office is closely monitoring the “associated buzz” around SMRs as a “promising source of carbon-free electricity” and awaiting more details, he and his team are more focused on “what we can realistically do to lower energy costs and create a more reliable energy ecosystem in the next five years.”

For Green, that “what” includes establishing a partnership with Japanese power producer JERA Co. Inc. to create a so-called bridge to energy sovereignty with more affordable alternative fuels like liquefied natural gas, or LNG, which is still a fossil fuel but burns cleaner and is more efficient than petroleum.

Proponents argue it would provide the grid with greater certainty while the state continues to make progress on a more renewable energy future. Opponents, though, say upgrades for LNG are a waste of money and a step in the wrong direction. Sherry Pollack, co-founder of 350Hawai‘i, says that LNG isn’t clean or cheap, and instead of solving the state’s energy challenges, it will exacerbate them. “The fossil fuel industry uses ‘greenwashing’ to market it as clean or transitional fuel, but every stage of the LNG life cycle spews potent greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere,” she says. “As for the touted lowering costs and building resilience, LNG would do the opposite. Price volatility of LNG is a well-established fact.

“Every dollar spent on LNG would move us backward by delaying our investment and transition to truly clean renewable energy.”

Green believes the state is making progress toward its mandates, and he points to an executive order he issued in January 2025 that seeks to hold the state to a more aggressive renewable energy timeline and streamline energy permitting. “The state’s plan is to partner with well-capitalized partners who share our values on affordability, energy reliability and a totally renewable and decarbonized future,” he says. “The state is keenly aware that O‘ahu is a more challenging place to achieve these objectives due to land constraints and population density. That’s why we cannot afford to further put off the push for more efficient power generation and cheaper, lower carbon fuels like natural gas.”

With none of the islands at self-sufficiency on renewables alone, Hawai‘i continues to import millions of gallons of crude oil each year to power what the State Energy Office has dubbed an “aging and largely inefficient power plant fleet.” In fact, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, petroleum makes up fully 90% of Hawai‘i’s energy consumption, more than any other state. (The state’s last coal-powered plant, which provided 20% of O‘ahu’s energy, closed in 2022.)

Problems with Our Current Energy Plan

Putting the problem in perspective, Hawai‘i has the third-lowest total energy consumption among the states, but still uses 16 times more energy than it produces, the EIA reports. Importing petroleum for electricity is not only costly and inefficient, it exposes the state to “multiple layers of fragility,” according to Sustainable Energy Hawai‘i, a nonprofit that’s working to make energy more affordable.

The state’s grid relies on market whims, and shocks to the system are all too common—from pandemics, disasters and violent conflicts in oil-producing nations. “It’s absolutely the worst way to produce electricity,” says Mark Glick, the state’s chief energy officer.

The Neighbor Islands, with their smaller populations and larger expanses of vacant land, have seen the greatest growth in renewable energy generation. In 2024, 59% of electricity generated on Hawai‘i Island was sourced from renewables, with geothermal energy contributing the biggest share (14%). On Maui, 41% of power generation is renewable; on Kaua‘i, it’s about half (mostly from utility-scale solar and hydroelectric systems). On O‘ahu, renewables comprise just 31% of the generated energy.

The Kaua‘i Island Utility Cooperative, one of the country’s newest utilities with about 30,000 residential and 5,000 commercial customers, says on sunny days it can operate its grid on 100% renewable generation for up to nine hours.

Lagging Behind Other States

Despite such progress, Hawai‘i trails the nation’s renewable energy leaders, by a lot. Some 92% of net electricity sales in South Dakota are from renewable sources, the highest percentage in the country. Meanwhile, Iowa is at 83%, Kansas 74%, and New Mexico 67%, according to a new analysis from the nonprofit Environment America Research & Policy Center in Denver.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimates Hawai‘i could generate the equivalent of five times its electricity demands each year from the sun alone and 12 times from wind. But tapping into those energy sources has proven difficult. And it will only get harder.

In addition to an aging electrical grid and the significant wildfire prevention investments and upgrades required in the wake of the Lahaina disaster, Hawai‘i is also facing rising energy needs with the electrification of the transportation sector and competing priorities for vacant lands, including housing and agriculture.

In June 2015, then-Gov. David Ige gathered environmentalists, lawmakers and Hawaiian Electric executives in his office to sign a first-in-the-nation law mandating 100% of electricity generation come from renewable sources by 2045. At the time, one-sixth of the state’s power generation was from renewable sources.

More than a decade on, Hawai‘i can celebrate how far it’s come in greening its grid.

Solar a Success

In Fall 2025, for example, Hawaiian Electric announced it surpassed 1 gigawatt of generating capacity from rooftop solar and battery storage connected across the state—roughly equivalent to the output of a large power plant.

In marking the milestone, HECO noted 44% of single-family homes served by the utility now have solar systems, one of the highest solar adoption rates in the nation. Solar panels have also become a frequent sight on the rooftops of businesses, government buildings and parking structures. And they’re making a difference—if not in people’s pocketbooks than toward achieving the state’s clean energy goals.

A city project to install solar panels and battery systems atop the Neal Blaisdell Center essentially resulted in the center becoming a net zero venue during the day. Other government buildings are hitting the same mark and saving on monthly utility bills.

Indeed, experts say, solar power has proven a boon for the sun-drenched Islands, doing much of the work in getting the state closer to its renewable energy goals. On O‘ahu, some 15% of electricity is generated from distributed (or rooftop) solar while 6% is sourced from utility-scale solar photovoltaic systems; 6% comes from wind.

But It’s Not a Complete Solution

While solar energy is cost effective, it’s not without downsides. For one, to be a viable option for large-scale generation, utility-scale solar projects need to be “firm,” which means they have to be consistent 24 hours a day. Without large (and costly) battery storage systems, solar is not considered firm—and neither is wind.

There’s also the concern about space: Large solar farms need lots of land and on O‘ahu, especially, that’s a problem. A 2025 Sustainable Energy Hawai‘i report that considered different energy future scenarios for the Islands concluded that a renewables portfolio relying on solar for about 80% of its net generation would require about 580 square miles of land to be set aside for photovoltaic solar systems. That’s about the size of the island of O‘ahu.

Colton Ching, Hawaiian Electric senior vice president of planning and technology, says there’s one more big problem with solar and wind. From January to March, Hawai‘i’s soggy winter months, solar and wind generation falls way off.

To address the drop-off, you’d have to “overbuild,” or install more photovoltaic solar systems than would otherwise be needed, Ching says.

And when it comes to wind, that could pose unique challenges. Onshore wind projects must take into account such factors as noise, shadows, and proximity to homes and schools. There are no offshore wind projects in the Islands, and while the state and HECO are interested in pursuing the idea, it’s far less likely one would get funding anytime soon because of opposition from the Trump administration.

The Pros and Cons of Geothermal

Ching says the ideal scenario would be to adopt a renewable resource that can produce “the power we need all year long.” What is that other energy source? One of the most promising candidates could be geothermal energy, says Nicole Lautze, a UH professor and director of the Hawai‘i Groundwater and Geothermal Resources Center. A recent report she co-authored found that, with public support and modernized policy, geothermal could be key to a balanced energy portfolio.

“Intermittent renewable energy can only get us so far toward our renewable energy objectives,” she says. “We have had an expansion of solar energy, but we haven’t seen much of a dent in the reliance of fossil fuels, and we’ve seen our electricity prices rise.”

There Are Obstacles to Geothermal Energy, Though.

The state’s only geothermal power plant, Puna Geothermal Venture on Hawai‘i Island, was completed in 1993 and currently generates about 14% of the island’s power needs. PGV has received approval to replace 12 older generating units with three new ones and then put in a fourth unit in a second phase of development. The upgrades are aimed at increasing the plant’s output by nearly 58% under a power purchase deal with HECO.

The State Energy Office says there is lots of room to grow geothermal on volcanically active Hawai‘i Island. However, PGV has drawn significant community opposition, including over feared health and safety concerns and from Native Hawaiians worried about desecration of sacred spaces and profiteering.

Addressing those issues is central to moving forward with any significant geothermal projects, says Ulupono’s Colón. “The way PGV was developed caused a lot of generational trauma for some folks and addressing that is important,” he says. “There needs to be an understanding that there are legitimate cultural concerns.”

Colón points to models of ownership that could benefit Indigenous communities and avoid divisive standoffs. In particular, he says, Hawai‘i could look at New Zealand and Maori-owned geothermal development projects.

Lautze also notes studies are underway or in the pipeline to determine whether geothermal is viable across our island chain. Her research indicates that Lāna‘i could host geothermal energy. “If there were enough geothermal resources, I think geothermal could stand alone,” she says. “But we haven’t made the investment to figure out if we have enough geothermal.”

Other Potential Sources of Energy

Biofuels, or fuels from agricultural crops, are also being studied as a potential source of renewable energy. But experts agree that vast tracts of land would be needed for it to supply enough energy and to be commercially viable.

“As the state forecasts toward 2045, most of the gap from solar energy is, right now, being filled by a combination of wind and biofuels,” Colón says. “But the cost of biofuels and the viability and community acceptance of wind are big questions.”

Dane Wicker, deputy director of the state Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, says the status quo is unsustainable, for households and the economy.

He urges residents to keep that in mind for the pain yet to come, as major changes to the grid translate into less-than-ideal realities in people’s backyards. “You still do have to address concerns,” he says. “But every community is going to have to undertake some infrastructure, whether housing, farming or energy.”

That might be where people like Stacey Alapai and organizations like the Upcountry Energy Resilience Project come in. Alapai says her goal is to help ordinary households reap real benefits from energy efficiency and sustainability projects. She says it’s why her group secured “second life” solar panels, replaced because they were no longer quite as efficient, for distribution to Maui wildfire survivors. A $40,000 grant from the Rotary Foundation helped cover the cost of battery generators along with some technical training.

“The goal here is to show people it’s possible,” she says, “and build from there.”

Solar

Much of Hawai‘i’s progress on its renewable energy goals is due to solar power; some 44% of single-family homes served by Hawaiian Electric have solar systems and roughly a fifth of power generated on O‘ahu comes from the sun. The problem with solar as a replacement to oil is twofold. For one, solar energy on its own isn’t “firm.” In other words, it can’t be relied on at all times to meet baseline energy needs. Battery storage is required to fill in the gaps at night and on cloudy days. Solar also needs space and, in the case of utility-grade farms, lots of it.

Wind

Getting a wind farm up and running isn’t easy. Developers must consider impacts on wildlife, nearby homes, schools and businesses, and elements such as shadow and noise. Still, wind is the second-largest contributor to renewable electricity generation in the Islands. When it comes to more growth, however, offshore wind projects don’t have the support of the Trump administration and onshore wind isn’t right for some areas. And like solar, it’s not considered “firm.”

Biofuels

Biofuels, which entail generating fuel from plant matter or even animal waste, comprise a small percentage of all renewable energy generation in the Islands. They could become a bigger player in years to come, including in the transportation sector, but the potential for biofuels grown and produced locally is constrained by land area and water availability.

Geothermal

Puna Geothermal Venture, near Kīlauea, is Hawai‘i’s only geothermal plant and recently received approval to expand its output, which accounts for about 14% of Hawai‘i Island’s electricity generation. But there are hurdles, including opposition from Native Hawaiians concerned about desecration of sacred spaces. Residents who live near PGV have also raised safety worries. It’s not yet clear whether geothermal could be an option for other islands since it would require funding to dig exploratory wells.

Nuclear

To weigh the risks and benefits of nuclear power, many are eyeing small modular reactors, billed as compact “neighborhood” nuclear reactors with more advanced safety features. The state Legislature is poised to discuss nuclear power in 2026, but moving ahead with such a project would face significant challenges, including overturning a state constitutional ban. Environmentalists are also ready to halt any nuclear project, citing concerns about how radioactive waste would be handled and stored.

Liquefied Natural Gas

LNG isn’t green, but it’s greener than petroleum, which is why the state sees it as a “bridge” to 100% renewable energy generation. Those who support moving to LNG say it would strengthen the grid, but opponents call that argument “greenwashing.” Last fall, Gov. Josh Green entered a partnership with Japan’s largest energy company as part of a plan to begin importing LNG. Experts say transitioning to LNG, though, would require billions of dollars in infrastructure upgrades.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen has been described as an energy “Swiss Army knife,” capable of being used in different ways. Currently, Hawai‘i Gas blends locally made hydrogen and renewable natural gas produced from the Honouliuli Wastewater Treatment Plant into its fuel mix delivered to customers. In 2026, a pilot project will test hydrogen storage and delivery in the Islands.