Keep Country, Country

A proposed gondola lift, zip line and all-terrain vehicle tours at Mount Ka‘ala are behind a fight pitting the North Shore and neighboring communities against outside developers who want to expand visitor attractions.

North Shore resident Denise Antolini can look out the window of her home office and take in the splendor that is Mount Ka‘ala. Home to a nature preserve, O‘ahu’s tallest peak towers 4,025 feet above sea level and remains mostly untouched save for agriculture, utility infrastructure and an access road.

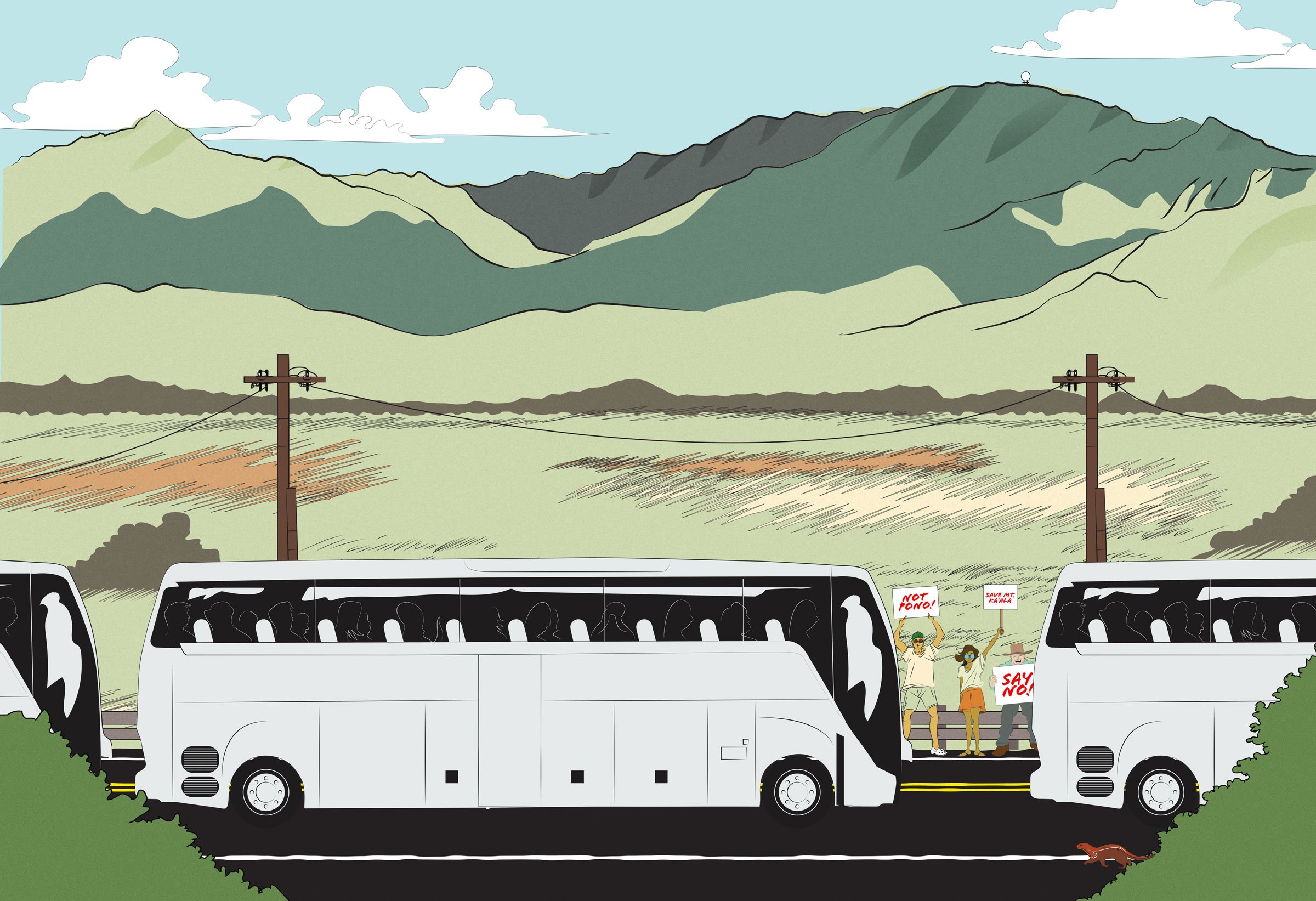

And if “Keep the Country Country” activists like her get their way, that won’t change. With roadside sign-waving rallies and emotional standing-room-only community meetings, a coalition of residents, environmentalists and elected officials are vehemently taking on a proposed “agritourism” attraction at Kaukonahua Ranch that includes a gondola lift at Mount Ka‘ala, a zip line, trails and all-terrain vehicle tours.

The project aims to bring in as many as 1,700 visitors a day to the rural area—approximately half the number that flock to Diamond Head State Monument. Amid a groundswell of protest, ranch owner Joey Houssian, a Canadian businessman and owner of an outdoor thrill-ride company in Whistler, British Columbia, has agreed to reel in the project’s footprint and pledged to fund reforestation and ecological preservation work.

But opponents aren’t appeased. They say a revised plan, which still includes the gondola lift, would mar an important natural and cultural landmark, disturb areas considered sacred by Native Hawaiians, and even threaten indigenous flora on the mountain, which the state notes is home to some of Hawai‘i’s rarest plants.

“Ka‘ala doesn’t need saving by a developer who’s planning a theme park,” Antolini says. The retired environmental law professor, talking from her Pūpūkea home on a recent afternoon, questions the reasoning behind the project. “Bringing an economic disturbance and justifying it as protecting the mountain is twisted logic. Ka‘ala is a centerpiece piko of the North Shore.”

Indeed, for many on the North Shore, the battle over the Mount Ka‘ala gondola project is about much more than an attraction or even a mountain. At stake, they argue, is the future of some of O‘ahu’s last undeveloped lands. The uproar also comes at a moment of growing concern about the quality-of-life impacts of tourism’s long creep outside of Waikīkī and a broader political conversation about what more “regenerative” tourism actually looks like.

While the Kaukonahua Ranch project is the most prominent example, several other planned tourism development projects are also generating ire. North Shore residents are raising red flags about a planned luxury development at Turtle Bay in Kahuku and a project that would add retail space along with housing in Hale‘iwa. And on the West Side, there is concern about a plan to build a $2 billion Atlantis resort at Ko Olina. The massive complex would be the first Atlantis property in the country.

While the projects are different, opposition to them is driven by a common theme. Residents say they simply can’t handle any more visitors on their roads or at their neighborhood beaches, stores and restaurants, and they fear these newer, large-scale projects threaten the very essence of Hawai‘i.

Kioni Dudley, vice chair of the Makakilo-Kapolei-Honokai Hale Neighborhood Board, says the Atlantis project is simply too big. With a proposed 1,324 rooms, he says the resort will also require thousands of employees and additional infrastructure. “The whole thing is just crazy,” Dudley says. “Absolutely insane. It must be stopped.”

Political analyst Neal Milner notes the tension between tourism and communities, including under the “Keep the Country Country” banner, is hardly new. What’s changed is a larger recognition, including from local government, that overtourism is exacting a heavy toll, especially on smaller communities, and that it must be better managed.

“The purpose of agricultural zoning is to support food production and food sovereignty, not to serve as a loophole for non-agricultural commercial activity. A gondola drawing over 1,600 visitors per day is not incidental to farming. It functions as a standalone tourist attraction, and that’s not what this land use designation was created to allow. The area borders protected conservation lands, including natural area reserves. ”

—McKenna Woodward, public policy advocate, Office of Hawaiian Affairs

Neighborhoods Unite

On an evening in late July, hundreds of people turned out at Leilehua High School for a special meeting of four neighborhood boards representing Mililani to the North Shore. On the agenda was one project: the Mount Ka‘ala gondola attraction. And while the project’s developer wasn’t there, attendees were adamant about voicing their complaints.

One after another, residents took turns at the microphone to convey their disappointment, concern, frustration and rage. Several choked up as they spoke; a few cried. And each speaker was followed by a roar of applause, shouts of approval and a waving of “Keep the Country Country” cardboard signs.

State House Majority Leader Sean Quinlan, whose legislative district includes Waialua, Hale‘iwa and Kahuku, summed up the mood of the crowd with one word: “Angry.”

“Maybe more than any one single factor, it is the sheer stupidity of what they are proposing that angers me,” Quinlan told attendees. “In this beautiful land, where you cannot even advertise Coca-Cola on the side of the road, they have proposed to sully the flanks of our gorgeous Mount Ka‘ala … with a motorized gondola.”

In response to the project, the lawmaker has proposed a bill that would ban gondolas outright on any Hawai‘i mountain. If approved, possibly next summer and signed by the governor, Quinlan contends the measure could quash at least part of the Mount Ka‘ala plan. The North Shore project has already received a city land use permit that allows for gondola activities, but the developer still needs to obtain building permits for any structures. In the meantime, grassroots protests are gaining momentum.

“The camel’s back is broken,” one resident said at the community meeting in July. “We’ve had enough.”

“Where does it end?” another asked the crowd.

Ann Freed, a member of the Mililani-Waipi‘o-Melemanu Neighborhood Board, told attendees the gondola fight wasn’t the area’s first antidevelopment battle and won’t be the last because the North Shore is worth fighting for.

“It’s the last bastion of open spaces that there is,” she said.

Project’s Scope Decreased

Aialua’s Kaukonahua Ranch covers about 2,400 acres; current owner Houssian acquired it from Dole Food Co. in 2017. The property is being used for cattle and to grow “trial” crops, including papaya, breadfruit, dragon fruit and bananas.

Kaukonahua Ranch first presented its “agribusiness” concept, called the Kamananui project, to the community in March 2018, outlining plans to put in a gondola, zip lines and other activities on the mauka area of the property. The city granted a permit for the project in 2019, and work picked up after the pandemic with community talks; engineering, architecture and traffic studies; and archaeological surveys. The project includes efforts to mitigate wildfires and protect threatened species, the developer says.

In response to a firestorm of criticism, Kaukonahua Ranch plans to pare down the original scope of its permit and has asked the city for modifications. Under the revised plan, the gondola would climb 1,250 feet up Mount Ka‘ala instead of 1,750. The number of gondola stations has also been reduced, from 18 to eight, and instead of four zip lines, the owner is proposing just one, which would extend 5,000 feet instead of the original 8,000.

Kaukonahua Ranch general manager Mark “Skip” Taylor says there’s no firm timeline for the Kamananui project, but the hope is to start work in the next couple of years. “We are optimistic that our (permit) modifications, which are minor in nature, will be approved as they are significantly reducing the scope of the project and integrating important community and professional design feedback we have received over the past five years, most notably around traffic and visual impact.”

Taylor says the gondola, zip line and other attractions are aimed at providing the public with “unprecedented access” to the land and educational opportunities while helping to support agricultural and conservation efforts, including the planting of native trees and clearing of invasive species. He adds a gondola was chosen because it has the “lowest ecological footprint” for moving staff, equipment, supplies and visitors to the upper valley areas of the ranch. “We are firm in our commitment to being good stewards of Kaukonahua Ranch,” Taylor says. “Importantly, our Kamananui project will create more than 200 much-needed jobs for North Shore residents and help support other area businesses.”

Taylor also points out the structures proposed in the project cover less than 2 acres of land within Kaukonahua Ranch. “The rest of our ranching operations will continue to be utilized for growing diversified agriculture, reforestation, habitat preservation and raising cattle,” he says.

Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting spokesman Curtis Lum says a review of the project’s permit modifications request includes input from residents. “The DPP is listening to community concerns and is committed to ensuring that agricultural activities are the primary, principal activities occurring on the site, and anticipated impacts aremitigated,” Lum says, adding the department’s specific concerns about the project were outlined as conditions to permit approval.

Those included protecting critical habitats, addressing traffic and managing erosion.

Keeping the Country Country

Honolulu City Councilmember Matt Weyer, whose district includes the North Shore, says the gondola debate reflects a broader push to preserve development-free space on O‘ahu and better manage tourism’s footprint.

He says the community isn’t against agritourism, but wants to see it handled responsibly. And he notes there are examples of low-impact agribusinesses that have community support, like horseback rides at Gunstock Ranch in Kahuku and tours of Little Plumeria Farms in Hale‘iwa. “For sustainable tourism, a lot of it is about management. We’re managing the space and managing the visitors,” he says.

As part of a $27 million contract from the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, the Hawaiian Council (formerly the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement) is working with local companies to consider how they might offer agricultural or ecological experiences to visitors. The contract, handled by the council’s Kilohana initiative, also includes funds for visitor education.

“For tourism to be embraced, the community is going to have to feel that it’s getting benefits beyond congestion, beyond development, beyond merely a drain on their resources.”

—Tyler Gomes, chief administrator of the Hawaiian Council’s Kilohana initiative

Tyler Gomes, Kilohana’s chief administrator, says regenerative or sustainable tourism must begin with community input. “Right now, a lot of the revenue that’s generated through tourism doesn’t stay in the state,” he says. “For tourism to be embraced, the community is going to have to feel that it’s getting benefits beyond congestion, beyond development, beyond merely a drain on their resources.”

He noted that when opposition to a project is as loud as it is in the case of Mount Ka‘ala, “that’s a signal that the community is probably hurting and does not feel that people are listening. The proponents should ask themselves: Does this community really need a gondola? Some introspection is a good thing.”

Milner agrees. He says “not in my backyard” is a knee-jerk reaction, and misunderstandings and a vocal minority have killed projects that might have benefited the community in important ways. But he says that’s not what’s happening with the gondola project. He says it’s been pitched as an “accessory use” to new agricultural production and broad preservation efforts, and that it “sounds like too much fancy frosting put over a cake that’s not very tasty.”

“It looks like you’re putting something up there to make some money,” he says.

State Rep. Amy Perruso, whose district includes Waialua and Mokulē‘ia, is among those who have been escorted to the Kaukonahua Ranch site by the developer to hear the proposal. “It was so clear to me—that is not a place that humans should be,” she says. “It’s an incredibly sacred, beautiful place.” But, she says, the project has a silver lining: It’s brought communities together, united by outrage.

“Keeping the country country is not just for fidelity to a slogan, but that area is fragile,” Perruso says. “It’s hard for the community to fight so many battles on so many fronts. This is a great opportunity for us to have deeper conversation.”

North Shore farmer and neighborhood board member Racquel Hill-Achiu is among those leading the charge against the gondola project. At the community meeting in July, she warned attendees they were in for a long fight.

“What we are trying to do is show both DPP and the developer that we’re not here to just lie down,” she says. “This mountain is the highest peak of this island and that alone is of great significance to all of us, regardless of where you live.”

For Antolini, the gondola battle is a big one—but not the only one. She says the question of overtourism, especially on the North Shore, is one that will require a lot more community involvement and public investment. “Regenerative tourism in my mind is that when a visitor comes, they actually give back through an activity,” she says. “To do real regenerative tourism, our community needs support.”

O‘ahu Pending Projects

Visitor attractions as well as housing and retail developments in more rural areas outside of Honolulu are sparking anger from residents.

1. Turtle Bay Development

Earlier this year, Utah-based Areté Collective kicked off construction of the first phase of a new luxury development at Turtle Bay. While Host Hotels & Resorts acquired the resort in 2024 and rebranded it as The Ritz-Carlton O‘ahu, Turtle Bay, Areté Collective purchased adjacent land from previous owner Blackstone Real Estate and has plans to develop 20 “resort residential units” in four buildings. Altogether, the project includes a total of 100 residential units and up to 250 hotel units, with plans to break ground on new phases in coming years.

Areté Collective says it has listened to community concerns about the project and has adjusted some of its plans accordingly, including narrowing the total scope, completing invasive species mitigation work and setting aside more square footage for open spaces.

But Jessica dos Santos, a Kahuku resident and member of the community group Kūpa‘a Kuilima, says there is still significant concern about the work. Residents, she says, are worried about impacts on traffic, infrastructure, native ecosystems and cultural sites.

2. Kamananui

A gondola scaling Mount Ka‘ala is the headline of a proposed “agritourism” attraction at Kaukonahua Ranch, but the plan also includes a zip line, café, all-terrain vehicle tours, and hiking and biking trails. Residents contend the Kamananui project would be an ecological disaster and a permanent blight on the island’s tallest peak.

The project’s developers, meanwhile, say they’re trying to preserve precious open spaces and natural resources by engineering an agricultural-focused nature experience for visitors. They also note that the project’s scope has been reined in based on community input and that requested permit modifications are before the city now.

The new plan includes fewer gondola stations, for one. The lift would also stop at 1,250 feet (from 1,750). And the ranch notes that the agribusiness structures would require less than 2 acres of land.

“Kaukonahua Ranch is an active ranch with existing cattle, forestry and crop operations and those operations are maturing and expanding constantly,” says ranch general manager Mark “Skip” Taylor. He says the expectation is that “the agribusiness project would commence in the next couple of years when all of our planning efforts are complete and permit conditions are satisfied.”

3. Hale‘iwa Backyards

How much development is too much for Hale‘iwa? For many residents, a project known as Hale‘iwa Backyards helps answer the question. Developer D.G. “Andy” Anderson wants to build a low-rise apartment with 150 units and 30,000 square feet of retail space on a 7-acre parcel in the town.

He argues the project is a win-win, providing housing and much-needed services. But opponents say Hale‘iwa Backyards will only exacerbate major infrastructure challenges in a rural community that sees thousands of visitors each day. In testimony to the City Council as it considered rezoning the agricultural land to urban, North Shore activist Denise Antolini pleaded: “Please listen to the community.”

4. Atlantis Resort (Ko Olina)

Most people don’t think of Ko Olina as “country.” But West O‘ahu residents say the resort area, home to a Four Seasons and Disney’s Aulani, among others, impacts their suburban and rural communities in several ways. And one of the biggest? Traffic.

That’s why residents didn’t exactly cheer news that a long-planned $2 billion Atlantis resort for Ko Olina is finally moving forward. Kioni Dudley, a member of the area’s neighborhood board, says the project is a bad fit.

“It would further exacerbate the freeway traffic problem,” he says. Dudley also worries about additional stress on the area’s infrastructure and natural resources, including its beaches, which is why he’s working to air community concerns.

The Atlantis would feature 800 hotel rooms and more than 500 luxury residences, along with an aquarium, wedding chapel and water park. It would be the first Atlantis-branded property in the U.S. and would be situated next to the Disney resort.

Asked how the project could be modified to fit with the area, Dudley replies, “It can’t.”

Residents Speak Out

In late July, the Wahiawā, North Shore, Mililani-Waipi‘o, and Mililani-Launani Valley neighborhood boards convened a community hearing with one agenda item: the Kamananui project at Mount Ka‘ala. Josie Hart Ka‘anehe, a law enforcement officer, was one of many area residents who voiced their concerns and objections to the proposed development:

“One day while I was driving on Kaukonahua Road toward Mililani, I was part of a life-threatening incident. A vehicle in the oncoming lane drifted across the center line. I could see that the driver had fallen asleep at the wheel. Thankfully, I was alert. I managed to swerve off the road into the pineapple fields, narrowly avoiding the telephone pole. This was a second experience for me that I had on that road. Years later, as a law enforcement officer, I responded to at least five fatalities on that same stretch of road. And now you’re proposing to increase the traffic in this area.

I also remember when Laniākea beach was untouched and serene. Then the word got out about the turtles. Now it’s overrun, crowded, littered, degraded. Is this the future that we envision for yet another beautiful and fragile place?

This is our home. Not every piece of land needs to be exploited to serve the tourist industry, especially when it comes at the expense of local safety, natural beauty and community well-being.”