Education Cheat Sheet: Helping Your Child with Math

Four ways you can support your child in math, even if you are afraid you won’t understand it.

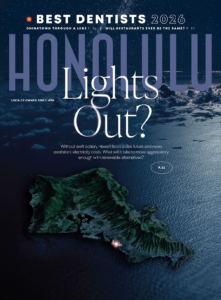

Photo: Courtesy of Island Pacific Academy

Editor’s Note: The thing I had feared since Cassera started elementary school happened in second grade. She asked me to check her math homework and as I stared at what appeared to be a timeline with jumps, backwards calculating and images, I had no idea what was going on. The way math is taught and calculated has changed since I was in school. So, if I don’t understand how my child is figuring things out, how can I help? Island Pacific Academy’s Stephanie Capen, Ph.D. has some advice.

When I meet someone for the first time and tell them I am a mathematics educator, I almost always receive the same responses. I hear about how much he or she hated math class in school, how bad he or she is at mathematics, and how mathematics just never “made sense”. As a mathematics educator I am always (not surprisingly) troubled by these responses. Humans are natural users of mathematics and often think mathematically. I firmly believe all students can be successful in mathematics.

Jo Boaler, Ph.D., professor of mathematics education at the Stanford Graduate School of Education wrote, “We want to see patterns in the world and understand the rhythms of the universe. But the joy and fascination young children experience with the mathematics are quickly replaced by dread and dislike when they start school mathematics and are introduced to a dry set of methods they think they just have to accept and remember…The inquisitiveness of children’s early years fades away and is replaced by the strong belief that math is all about following instructions and rules.” Traditionally, when students struggle to accept or memorize those procedures and rules, they often decide they just are bad at mathematics. In other words, they develop what Stanford psychology professor Carol S. Dweck called a “fixed mindset” about their ability succeed in math.

The good news is that educators have been responsive to emerging research and are changing how schools think about the teaching, learning, and assessment of mathematics. In addition, instead of focusing on algorithms and rules, they’re emphasizing conceptual understanding, problem solving, and reasoning and sense making. Evidence for this can be seen in the Common Core Standards for Mathematical Practice adopted by 42 states and the District of Columbia. Mathematical tasks are now designed to evoke deeper thinking, provide multiple modes for students to justify their thinking—through visual, written explanations, oral presentations, class discussions—and to have several ways students with various knowledge backgrounds and experiences can access the content. For many parents this shift in approach can be challenging and frustrating, particularly when their child comes home with questions on their homework that look different than the questions parents received when they were kids. Here are some tips that I have found to be helpful for parents in supporting their child’s learning of mathematics.

Parent’s Homework:

- If you see your child struggling to arrive at a solution, remind them that challenge is good and an important part of learning. Contemporary research has actually shown that our brains grow when we struggle and make mistakes (whether we know we made a mistake or not!). Boaler said, “The power of mistakes is critical information, as children and adults everywhere often feel terrible when they make a mistake in math. They think it means they are not a math person, because they have been brought up in a performance culture in which mistakes are not valued—or worse, they are punished.” Mathematics educators want students to problem solve and that often involves making mistakes along the way. In my own classes I never expect students to come with a correct answer, but I expect them to come with ideas they have developed and ready to share those ideas, so that we may arrive at a solution together. I know it can be hard to watch your child struggle, but remember if you tell your children the answer, or how to solve the problem, they miss out on an important opportunity to discover the solution for themselves.

- Ask them to explain, in words, their method or solution and justify each step. Have them write, again, in words, how he or she thought about the problem and why he or she feels the method for solving is appropriate or the solution is reasonable.

- Have them draw a visual representation of their thinking. Sometimes creating diagrams, graphs, or sketches can help students see the problem more clearly.

- If your child is stuck on a problem, here are some helpful questions to ask:

- What are some things that you know from the problem? How do you know this? (Have him or her write this down.)

- What are you unsure of? Why?

- Have you seen a problem similar to this? How might looking at that problem help you? Is there anything in your notes that might help you? (Have him or her look)

- Is there a question you would like to ask about this problem? (As a math educator, I love when students come to class with great questions!)

Stephanie Capen, Ph.D. is the secondary curriculum coordinator at Island Pacific Academy and has taught high school mathematics at both the University Laboratory School (where the questions in Tip four were developed) and Maryknoll High School.

Want to know more?

For more information, videos, and resources, check out Jo Boaler’s website https://www.youcubed.org/.