Not a Foodie

Despite our similarities, my dad and I had very different tastes.

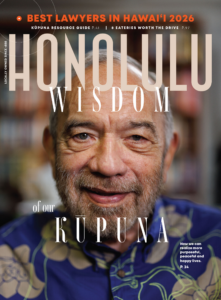

Illustration: James Nakamura

I didn’t eat curry until I was in college. I blame my dad for this.

The man was not an adventurous eater. On a family trip to Japan, he searched the Family Marts and 7-Elevens for blueberry muffins and hot dogs, overwhelmed by the unfamiliarity of offerings. He’d try new things occasionally, but he liked what he liked—things like steak, pasta and good ol’ American standbys—and if that isn’t one of the dad-iest stereotypes, God help me.

My parents came from a Canadian town that today only has about 2,000 residents—hardly a cultural center the way Honolulu is. But I grew up here, with a world of culinary possibilities. I didn’t really go out to eat much until college, when I started spending more time with friends than with family. And they wanted to go to places like Curry House and Pho 777.

I started eating so many new things, from squab to al jjigae to lamb biryani. Soon enough, I began cooking new things too, excited to explore a wide range of cuisines. It made me feel more integrated, an active participant of life here.

Almost anytime I made lunch in the past few years, my dad would wander into the kitchen with his nose turned up. I’m making kim chee grilled cheese, I’d tell him.

“Why would you do that to a perfectly good grilled cheese?” he would sneer.

“This is what happens when you raise your children in a place like this!”

He was giving me a hard time as dads often do. But I felt the difference between our upbringings as I pickled daikon, heated up a jar of Kashmiri curry and added fish sauce to my soup. There are innumerable ways I was like my father, but this was, perhaps, the biggest divergence.

“Why would you do that to a perfectly good grilled cheese?” he would sneer.

The way I experience other cultures is how I find my place among them, and food is a big part of that. Not for Dad. On a recent trip back to Canada, my heart swelled to see the way he interacted with old friends and family. They laughed about adventures of their youth as he proudly pointed out all the places he got into trouble. Though he lived in Hawai‘i for 30 years, he didn’t have that same circle of others around him here—certainly not a circle as diverse as mine. Maybe if he did, he wouldn’t have always given me such a hard time about my food preferences.

When my dad died unexpectedly in August, my family used DoorDash to bring us things like tofu and pho from Chopstick and Rice. We started cooking Thai food multiple times a week—things Dad wouldn’t even want us to have in the house if he were there. We mumbled apologies as we ate his least favorite foods while sitting in his chair, almost as if we were gloating.

But I also ate his English muffins to clear out the fridge, drank his Heinekens, telling myself I’d much rather have something from Beer Lab HI, but relishing the small connection I could still make with him. There’s a calamansi tree he planted in our yard (and loved); for good measure, I grabbed one of the fruits and squeezed its juice into the bottle.

Now that he’s gone, I attempt to use the smell of kim chee to lure his spirit from beyond, to come into the kitchen and deride my lunch, just one more time. The quiet sizzle of the cabbage in the pan whispers nothing. I still like kim chee, of course, but eating it isn’t as fun as when I would use it to brag to my dad about how much more local it made me.

But it’s thanks to him. Maybe he didn’t agree with my tastes, but they exist because he and my mom chose to raise me here, where my options for pretty much everything are vastly wider than in my hometown. Behind his taunts, I like to think there was a hint of pride that I became part of this community. So thanks, Dad, for everything.

Katrina Valcourt is the executive editor of HONOLULU Magazine.