Hawai‘i’s Historic Homes

They reveal our past and offer a richer understanding of who we are. We look at three neighborhoods full of these gems.

You may be familiar with the bronze “historic residence” plaques prominently displayed outside some O‘ahu homes. They’re a visible designation of historic properties, a half century or older, on the state’s official register.

While some are linked to such notable architects as Vladimir Ossipoff, Charles William “C.W.” Dickey and Albert Ives, others reflect celebrated styles, perhaps a 1920s plantation home, a Tudor or a midcentury modern. Many have noteworthy past owners or an intriguing backstory.

“If the architecture, engineering or construction are in some way significant and have characteristics that tell a story about building and design of a particular time and place, it can qualify,” says Kiersten Faulkner, executive director of the Historic Hawai‘i Foundation.

The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 set up a nationwide program to recognize historic properties. It also enabled states to develop their own programs. The Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places, celebrating its 50th anniversary next year, arrived a decade later. “It’s a way to help people understand the roots of a community, telling stories of the people,” Faulkner says.

Without appreciating historic markers, we’re settling for a superficial understanding of who we are, says Honolulu architect Glenn Mason, whose Mason Architects firm specializes in historic consulting and restorations. “We would have no knowledge about how to move forward in the future.”

The Official Designation

To be placed on the state register, which provides a significant property tax exemption designated by each county, homeowners must go through an extensive process to confirm their home’s historical importance and gain approval from a review board. This requires deep research, a task homeowners can take upon themselves or outsource.

Once approved, the property must remain publicly visible (no barricading gates or walls), and owners cannot demolish their homes. They’re not restricted from modernizing or remodeling, but they need state approval for both interior and exterior projects. Failure to meet conditions can result in penalties, including payment of any taxes they might have been exempt from.

According to the state’s Department of Land and Natural Resources, which administers the program, the Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places includes 1,127 properties. Of these, approximately 400 are houses or residences; 340 of them are on O‘ahu, 37 on Hawai‘i Island, 12 on Maui, and 11 on Kaua‘i.

Mary Kodama, architecture branch chief at the State Historic Preservation Division, says those numbers represent just a fraction of the homes that might be eligible.

While scanning O‘ahu’s list of officially designated historic homes, it’s clear the majority are concentrated in older, wealthier neighborhoods like Mānoa, Nu‘uanu and Diamond Head. According to Mason, it’s because homeowners in these areas tended to have the financial resources to hire renowned architects to design notable homes to match their personal tastes.

“We have to be honest that it was an old boys club,” he says. “People who had money hired architects they knew. It’s not an accident that Ossipoff got to design the Outrigger Canoe Club and the Pacific Club and did Thurston Memorial Chapel at Punahou. He knew people.”

So, Are Historic Homes Coveted Real Estate?

Yes and no, Mason and Faulkner say. While some homebuyers truly appreciate the history and charm of older homes, others want modern homes. “Some buyers might think, ‘Wow, this is pretty cool. Look at that weird little cupboard over there,’ and admire all the things that are sometimes present in old houses,” Mason says. “But there are others who look at a property and see the restrictions from a historic designation as … controlling or limiting of what they want to do with the property.”

The Historic Hawai‘i Foundation now works with the Honolulu Board of Realtors to offer guidance on what it means to buy, sell and live in a historic home, in the hopes of helping Realtors avoid buyers who might want to tear them down, even though the home would lose its historic designation.

The designation, after all, should be deemed as something special, Kodama says. “It should give the homeowner a sense of pride.” —DS

* * *

Nu‘uanu

A Step Back into Old Honolulu

Some of Nu‘uanu’s historic homes are united by thoughtful design that incorporates the natural environment.

By Katrina Valcourt

Just past Nu‘uanu Valley Park, more than a dozen homes with historic designations sit within a mile of one another, many built as part of Dowsett Tract after Pali Road was constructed early in the 20th century.

Back in the day, the neighborhood’s proximity to Nu‘uanu Stream, Downtown and Honolulu Harbor appealed to government officials, wealthy business owners and other well-to-dos, who tapped some of the most noted architects of the time to build their homes.

But let’s go back even earlier.

After 1795’s destructive Battle of Nu‘uanu, the area was converted to lo‘i kalo. “The ‘auwai, the ditches that irrigated fields, are still there. And they run through the front yards of all the homes built in the ’20s and ’30s as landscape features,” says Kiersten Faulkner, executive director of the Historic Hawai‘i Foundation. Walking along Dowsett and Alika avenues, a steady burble is almost always audible as the ‘auwai snakes along the side of the road, sometimes no more than a foot wide and a few inches deep.

“There’s an ‘auwai committee that’s trying to bring back interest in the ‘auwai system, and that was kind of a passion project for my family,” says one longtime homeowner in the area who didn’t want to be identified. She says that maintaining a legacy of Hawaiian culture honors her family’s ancestors and the land. “The really lovely thing about it is it is a real connector for the community. It’s a great way to meet neighbors and to have this shared purpose. … There’s this water flowing through our properties that connects us in a really special and deep way.”

The home, on the Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places since 2003, was built and designed by Catherine Jones Richards, Hawai‘i’s first licensed landscape architect, and her husband, Russell. Known for designing the courtyards and grounds of the Honolulu Museum of Art, Ala Moana Beach Park, YWCA Laniākea and more, Richards “had to have been the only female landscape architect in town,” says Glenn Mason of Mason Architects.

The 1921 home, built in Colonial Revival style, was adapted for Hawai‘i with clapboard siding, high ceilings, large windows and French doors that allow for airflow and light. You’ll see similar elements at the nearby Thomas Victor King House, built in 1918; the Isabelle Jones House, built in 1924 by Richards’ mother; and the Louis and Marjorie Stephens Residence, built in 1926, among others.

“You can see everything from this definitive moment in Hawai‘i’s history (the Battle of Nu‘uanu) to consulates that were built after World War II when Korea and the Philippines and Japan wanted to have a presence for trade.”

Farther mauka, the homes are more Spanish Colonial Revival and Spanish Mission Revival—different names for similar styles. “Typically, they don’t have big overhangs; they have stuccoed walls and whatnot. They’re fairly plain-looking on the outside,” Mason says. The Mediterranean climate is similar to Hawai‘i’s, so people thought “that kind of architecture could be transplanted here.”

Former Gov. George Robert Carter’s old house, called Lihiwai, was constructed in this style in the late 1920s out of bluestone and concrete with an Otis elevator, multiple fireplaces, ‘ōhi‘a flooring and other design elements befitting of the most prominent members of society. It was built by architect Hardie Phillip, who also worked on the Honolulu Museum of Art and C. Brewer Building.

A few years later, more homes were being built across the stream. The Purvis Residence—a Spanish Mission style home built for a Bishop National Bank vice president—was designed by C.W. Dickey in 1930, though without the signature roof for which he would become known. In 1934, Dickey built a home for James L. Coke, a former Hawai‘i Supreme Court chief justice. Known as Waipuna, the Colonial Revival house itself isn’t as impressive as its yard, which was designed by notable landscape architect Richard Tongg in the 1930s. It includes both an ‘auwai and Nu‘uanu Stream running side by side and once featured lily and koi ponds with dozens of other plants.

On either side of the Kimo Drive bridge, you can see these waters and imagine all that has occurred along the stream’s path, from its source in the valley all the way down to Honolulu Harbor. “You can see everything from this definitive moment in Hawai‘i’s history (the Battle of Nu‘uanu) to consulates that were built after World War II when Korea and the Philippines and Japan wanted to have a presence for trade,” Faulkner says. “To me, that’s what’s amazing about Nu‘uanu. Other places have layering, but you see that so explicitly there.”

* * *

Diamond Head

The Lure of Lē‘ahi

It’s long been home to prominent homeowners with the means to build notable homes in diverse architectural styles.

By Diane Seo

With its proximity to Kapi‘olani Park, world-class beaches and killer ocean views, Lē‘ahi (or Diamond Head) has long been a haven for well-to-do residents. As such, when the area’s neighborhoods were first developing in the 1920s, some of Hawai‘i’s most distinguished architects were commissioned to design its homes and condos.

Today, several residences along Kalākaua Avenue, Hibiscus Road, Kiele Avenue and other Diamond Head streets display plaques indicating their inclusion on the Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places. “Diamond Head is loaded with historic homes because it was one of the earliest residential areas, and it’s where people with lots of money always have gone to develop homes,” says Glenn Mason, whose architectural firm has taken a leading role in preserving historic properties.

And while not all residences are grand—some are modest-sized bungalows and cottages—Diamond Head is the clear opposite of a so-called “cookie-cutter” community. Rather, its historic homes span a range of distinctive architectural styles. “The property owners often had a custom house built, so it was very individualized,” says Mary Kodama, architecture branch chief at the State Historic Preservation Division.

During a walking tour of the area’s historic homes, here’s what you might encounter: double-pitched roofs by architect C.W. Dickey, often referred to as “the Dickey roof”; regional, plantation-style beach houses popular from the 1920s through the 1940s; Spanish Mission Revival residences; and European Tudor homes, some in a storybook style and referred to by those in the neighborhood as “gingerbread homes.”

“We should be retaining historic homes, otherwise, you lose a lot of the charm of Honolulu.”

A cluster of 15 properties—mostly in Diamond Head, but elsewhere, too—gained historic designation as a group. Built between 1923 and 1932, they are “highly stylized, ‘Olde English’ or French Norman design styles that often include asymmetrical massing, half-timber and stucco façades, casement windows with diamond panes, and either high-pitched roofs or roofs with rounded eaves in imitation of thatch,” according to a description of the homes on the Historic Hawai‘i Foundation website.

Liz Perry, a Realtor, lives in and owns an oceanfront “gingerbread” home that’s part of the designated cluster—a 1932 French Tudor along Kalākaua Avenue that she adores for its playfulness. Indeed, the three-bedroom, three-level home exudes whimsy with its with its wrought-iron stairwell, diamond-paned windows and many other unique features.

“It wasn’t meant to be a mansion … to me, it has more personality,” Perry says. “It’s just the right size to me, not large, but I have my bedroom on the third floor, and I’m able to have house guests on the second floor.”

Along with her stunning ocean views, she loves the tight-knit neighborhood. “We should be retaining historic homes, otherwise, you lose a lot of the charm of Honolulu,” she says. “Every day, all day long, people come into the courtyard to look at our homes. They’re walking to Diamond Head, maybe from Waikīkī, and we’re part of their tour.”

A block away, on Kiele Avenue, Tony Cannariato and his wife, Sharon, bought a 1928 Storybook Tudor Revival home that was deemed at the time a tear down. It was 2021, and instead of building from scratch, they decided to restore the original structure and get it approved for the state’s historic register. During the application process, the Cannariatos discovered their home had a distinguished past owner—William Kanakanui, a Native Hawaiian who graduated in 1924 from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and served in the Navy as a commissioned officer until he retired in 1947. As a Punahou student and at the Naval Academy, Kanakanui was a standout swimmer.

Cannariato beams as he tells the backstory and says despite the years it’s taken to rebuild the home to its original glory—and it’s not finished yet—he and Sharon have always loved historic homes. “We were looking for something with character, and we like this cottage-looking design,” he says. “It’s the reason we’re in this neighborhood, because of the charming architecture.”

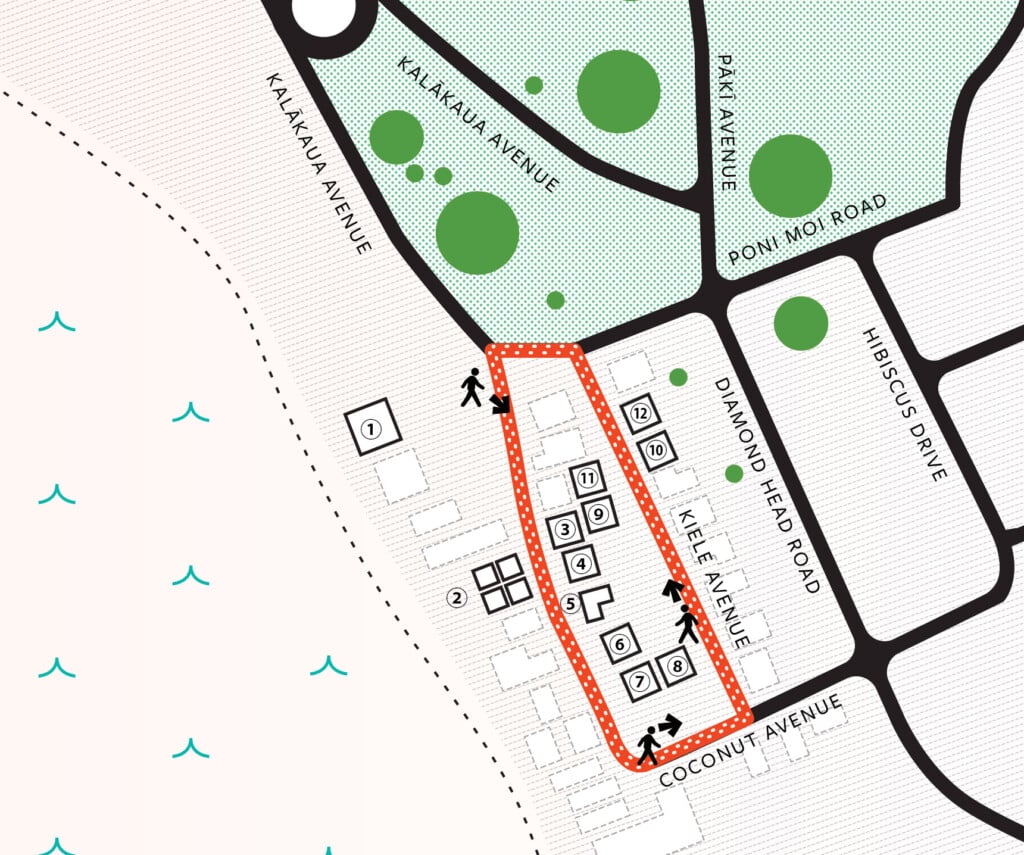

Gold Coast Walking Tour

On Oct. 14, 2023, AIA Honolulu chose the Gold Coast, including parts of Diamond Head, for its annual walking tour. The group toured both midcentury condos and historic single-family residences from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The descriptions featured here were provided by AIA Honolulu, the local branch of the American Institute of Architects, with some editing.

Note: The AIA tour included several other places, beyond homes, but we focused on residences listed on the Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places. It doesn’t include all Diamond Head homes on the register but offers those on foot the opportunity to see a sampling of homes.

1. The Tahitienne

2999 Kalākaua Ave.

Architects: Bob Fraser, Paul Hammarberg, Edwin L. Bauer

Year built: 1958

The only Gold Coast condo on the Hawai‘i Register of Historic Places, this modern, utilitarian and asymmetric building reflects Hawai‘i during a co-op building boom in the 1950s.

2. Tudor/French Norman Cottages

3000 block of Kalākaua Avenue, and other areas

Architect: Earl Williams, Hart Wood, John Morley, Theo H. Davies & Co., J. Alvin Shadinger

Years built: 1923–1932

This collection of French Norman-style residences reflects the influence of California, where houses like these were popular at the time. Fifteen separate residences remain in Honolulu, several on the Gold Coast. The style typically is distinguished by asymmetric massing, a mix of timber and stucco in the façade, diamond-pane windows and high-pitched roofs with rounded eaves that imitate thatch.

3. Egholm Residence

3022 Kalākaua Ave.

Architect: Carl William Winstedt

Year built: 1926

The residence is one of Honolulu’s few examples of a small cottage in the Spanish Colonial Revival, a popular style suitable for Hawai‘i’s warm climate. The brick, stucco and red clay roof tiles are common characteristics of the style.

4. James J.C. Haynes Residence

3026 Kalākaua Ave.

Architect: Ray Morris (Lewers & Cooke)

Year built: 1926

This home sits on a unique lot, larger than most in the neighborhood, spanning both Kalākaua and Kiele avenues. The well-built Colonial Revival home incorporates detailed craftsmanship with wood-shingled exterior walls and Colonial detailing.

5. C.W. Dickey Residence

3030 Kalākaua Ave.

Architect: C.W. Dickey

Year built: 1926

This residence is a quintessential example of the double-pitched, hipped roof that represented a distinctive Hawaiian style of architecture at the time. The cottage features some early Dickey trademarks such as large overhangs, board-and-batten siding, and stained concrete flooring.

6. Doctor Frank & Kathryn Plum Residence

3044 Kalākaua Ave.

Developer: Rudolph Bukeley

Year built: 1929

The home is an example of a Cotswold cottage, a type of Tudor Revival style popular at the time. It’s represented by romantic asymmetric massing, a skewed gable roof over the entry lānai, round arched openings, and an overall whimsical appearance.

7. Fred Harrison Rental Property

3050 Kalākaua Ave.

Builder: Fred Harrison

Year built: 1923

Fred Harrison was a prominent local builder who built this home as an investment for his family. It represents a typical middle-class rental of the time, characterized by a sweeping roof line, bay window, double gable ends and a front entry door not facing the street.

8. Marion & Samuel Steinhauser Residence

3043 Kiele Ave.

Architect: Hart Wood

Year built: 1938

Designed by Hart Wood, one of Hawai‘i’s most influential architects, the residence is an example of the 20th century Monterey style with its steeply pitched side-gabled roof, stucco walls and cantilever portion of a second-story porch.

9. Adolph Egholm Kiele Avenue House

3023 Kiele Ave.

Architect: Carl William Winstedt

Year built: 1926

This Adolph Egholm house, a Spanish Mission Revival cottage, is a single-story home with stucco walls, a red clay tile roof and a round-arched arcade.

10. William & Edna Montgomery Residence

3014 Kiele Ave.

Building supplier: Lewers & Cooke

Year built: 1926

This pavilion-style home with Mediterranean influences and touches of European tradition features stucco walls and Tuscan columns on the lānai.

11. Gobindram Watumull House

3015 Kiele Ave.

Architects: Dahl & Conrad

Year built: 1939

This residence has characteristics of the modern style, including acid-stained concrete floors, curved walls, built-in cabinetry and corner sliding windows, but with adaptations for Hawai‘i. Typical modern buildings have flat roofs. Here, the wide overhang provided by a hipped formation provides shade.

12. Mrs. Josephine Ketchum Residence

3004 Kiele Ave.

Architect: Not listed

Year built: 1931

This Craftsman-style bungalow, adapted for Hawai‘i, has naturally stained board-and-batten walls, with heavy timber elements that accentuate horizontal features, all characteristics of the Craftsman style. Hawai‘i-specific adaptations include a complete double-pitched hip roof, screened lānai and an exterior bathroom door.

* * *

Mānoa

A Proud Past

Mānoa’s historic homes cut across the valley, connecting the community to its rich history.

By Darlene Dela Cruz

Once a popular retreat for Hawai‘i’s ali‘i, Mānoa has long been one of O‘ahu’s most desired residential neighborhoods, with its lush valley setting, cooler temperatures and proximity to Honolulu’s urban core.

Along with attracting royalty like Queen Lili‘uokalani and Ka‘ahumanu, a queen consort to Kamehameha I and later queen regent, Mānoa has drawn a diverse range of residents over the centuries, including plantation workers, as well as families and faculty of Punahou School and the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

As one of the island’s oldest residential neighborhoods, Mānoa has retained its vintage charm, reflected through its many historic homes. Across the valley are classic Tudor residences; contemporary midcentury homes by architect George Wimberly; and residences designed by Hawai‘i regional architecture pioneer Hart Wood and Ted Vierra, one of the Islands’ first Native Hawaiian architects.

Built in 1929, Hale Huelani is a historic Craftsman cottage in upper Mānoa that once was home to Earl M. Welty, a notable local newspaper editor and radio broadcaster. Its current owners, who wished to remain anonymous, have made a conscious effort to preserve the home’s classic features, including wood planks, canec walls and vintage hardware. One of the homeowners’ favorite features is the chimney, which has four red bricks that stand out against its lava rock construction. “Another very nice feature [in the home] is the large eaves,” the homeowner says. “You can keep your windows open all the time without the rain coming in.”

Maintaining Mānoa’s distinct architecture and character is a priority among residents, says Linda LeGrande, a board member of Mālama Mānoa, a nonprofit with a mission to preserve historic Mānoa. She describes the valley’s lush setting as unique, blending urban life with the natural beauty of the Ko‘olau. “We have a defined mountain range that encompasses our valley, and it’s like the arms that encircle and hold us,” she says.

LeGrande, who lives in a state-designated historic home, was among those who launched the organization’s first historic homes walking tour in 1996, with 66 attendees. In 2019, the last time the tour was held, about 450 people took part. That tour featured stops at homes representing different architectural styles, including Craftsman, Colonial Revival, Late Victorian Single, Queen Anne, Prairie, and Georgian Revival with Italianate influences.

LeGrande says the tour became more popular with growing public interest in older architecture, especially styles from the 1920s through the midcentury era. She says people were also curious about notable past residents who contributed to the development of Honolulu. Although the pandemic-initiated hiatus has been lengthy, LeGrande hopes to resume the tour soon.

She says Mānoa’s historic residences strengthen the neighborhood’s sense of identity and connect the community to its rich past. She hopes to one day have the area’s historic College Hills tract added to the National Register of Historic Places. “When you document a neighborhood—when you describe it and define it—it gives people something to be proud of,” she says.

* * *

Mānoa

Modest, But Infinitely Rich

It’s the type of home where her parents might have worked when they were a chauffeur and a house servant.

By Mari Taketa

On East Mānoa Road, George and Ruth Tokumi’s 1915 Craftsman-style bungalow appears modest compared to the valley’s stately mansions. But its designer was Oliver Traphagen, architect of the Moana Surfrider, and like other masters of his craft, Traphagen filled the interior with rich detailing. With coffered ceilings, an Italian-tile fireplace and stained glass roses on built-in hutches framing the dining room, it’s an officially designated historic home—the kind of house, Ruth Tokumi says, where her parents might have worked when they were a chauffeur and a servant.

Instead, they ended up buying it. With few options after the Great Depression left him jobless, Shoichi Okahara and his wife, Tsutomu, opened a saimin stand at the edge of Chinatown. The success of Okahara Saimin fueled expansion to a wholesale factory on Waiola Street in McCully, where the couple lived and raised seven children. The story might have continued along this trajectory, except in the late 1940s, Tokumi’s older brother died, and to ease their grief with a fresh start in a place without memories, her parents bought the house on East Mānoa Road.

Tokumi is in her 90s now. As stewards of the house for the extended Okahara ‘ohana, she and George renovated it, enclosing the wraparound lānai to create a large family room and a fourth bedroom. In her younger years, Tokumi opened the home to Historic Hawai‘i Foundation tours, pointing out the boxy layout devoid of hallways, scraps of original fabric wallpaper in a flowing Art Nouveau floral pattern, the renovated cottage and maid’s quarters behind the garden. When the guava tree fruited, Tokumi froze the purée to make juice year-round. When the Okahara clan gathered for the holidays, she got out her mother’s potato masher and made creamy mashed potatoes at Thanksgiving and sekihan, sticky red-bean rice, at New Year’s. She’s pulled back in recent years and the house is quieter now, more modest than ever in today’s Mānoa. But it’s still rich inside.

* * *

Makiki

A Smaller, Closer Honolulu

On the slopes of Punchbowl, homes on tiny Clio Street preserve the look of working-class 1930s Honolulu.

By Mari Taketa

“The Clio Street gang?” my friend says when I ask if she’s related to one of the original homeowners on the cozy lane. “They were infamous. You could walk into any house. And they had this huge party at Christmas.”

Her reaction bears out Melvin Chang’s stories about the tiny neighborhood on the slopes of Punchbowl. In 1929, City Mill bought the 10 lots lining Clio Street, and over the next dozen years filled them with bungalow-style homes whose Chinese families formed a tightknit community. Chang’s parents, Dai Chin and Betty Chang, bought No. 1117 with its gable-roofed porch, lava rock shoulders ascending the front steps and prayer nook behind the kitchen, and planted a fruit tree after the birth of each child. The lychee tree in front celebrates their youngest, Mel.

Now 75, Chang stands under the lychee leaves, pointing at original and remodeled homes around him. “That was the Chars, that one was Lum, the Yees still live there,” he says. All the houses are within earshot. It wasn’t uncommon for neighbors to walk the block, calling out to see who was free for mahjong. Behind the Changs’ house, under avocado and mango trees, Dai Chin tore down his garage and replaced it with an open-air patio to host decades of Clio Street Christmas parties. All the families came, the fathers taking turns playing Santa Claus, and when the children grew up and moved away, they came back and brought their kids to those parties.

That era ended years ago. Today, kids you see on the quiet sidewalks are apt to be students from Roosevelt High School, retrieving their cars after classes. Except for this and the smattering of renovated homes, Clio Street is a time warp, a visual throwback to the smaller, closer working-class neighborhoods of 1930s Honolulu.

How to Research Your Home

Curious about whether your home qualifies for the state’s historic register, or want to know more about it? The Historic Hawai‘i Foundation and National Park Service offer resources to research your property’s history. Find them at historichawaii.org/how-to-research-the-history-of-your-home, along with a helpful webinar. Here are tips to get started:

- Search your address online.

- Ask neighbors, previous owners or their relatives about what they remember, including what the house may previously have looked like.

- Find real property tax records at realproperty.honolulu.gov. You can also find information about land parcels and maps at honolulugis.org. These are free online.

- The Hawai‘i State Library has city directories, newspaper archives and phone books that list who lived in the home—not just owners, but renters, too.

- Others who may have researched homes in your neighborhood can provide clues about yours, especially if they were built around the same time.

- Don’t underestimate social media. Neighborhood groups, real estate agents and others may have already done research, giving you a head start.

- Keep organized notes, including sources of information.

- Verify information with primary sources if possible.

If your home is historically significant—whether it’s because of architecture, association with individuals or some other reason—and hasn’t been majorly altered, you can submit a nomination form to the Hawai‘i State Historic Preservation Division. The process typically takes a year or more. —KV

Buying or Selling a Historic Home

While historic homes can have obvious appeal, you should be aware of the pitfalls of owning one—and understand what you can and can’t do to the property—before you buy.

“Some people love historic homes, and that’s who you want to live in a historic home,” says Kiersten Faulkner, executive director of the Historic Hawai‘i Foundation. “Some people don’t like historic homes, and you really don’t want them to buy a historic home because it’s not going to meet their needs and then they won’t be good stewards for it.”

Glenn Mason of Mason Architects remembers when a Diamond Head homeowner looking to hire his firm didn’t care about the home’s significance. “That owner told me what they wanted. And I said, you can’t do that with this house,” he says. “They demolished the house. It was on the register, and they demolished it because they weren’t interested in keeping the historic look. They wanted what they wanted.” It isn’t illegal to demolish a historic home, though there may be repercussions such as fines if the proper process isn’t followed.

When shopping for a historic home, first look for documentation that proves it’s on either the Hawai‘i or national historic registers. If it’s receiving a tax exemption, get familiar with the requirements for continuing to receive it. You should also read the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for the Treatment of Historic Properties. You’re still allowed to renovate and add things like solar panels, but all interior and exterior projects requiring building permits must be approved by the State Historic Preservation Division.

When selling a historic home, if its historic designation is important to you, find a real estate agent who aligns with these values. The Historic Hawai‘i Foundation works with the Hawai‘i Board of Realtors to offer guidance and connect the right property with the right buyer.

“It’s that matchmaking,” Faulkner says. “We want to provide this information to the Realtors so that they can provide it to their clients, and so they can provide better service to everybody.” —KV