Kō Hawai‘i: Belonging to Hawai‘i

We need to recognize that our strength is the love we share for our Island home.

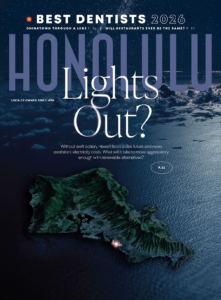

Photo: Andrew Richard Hara

Kō Hawai‘i means to belong to Hawai‘i. It’s a way of identifying with our Island home. It is, however, far more complex than a label because it’s based on our aloha for and relationship with our ‘āina (land), kai (sea) and po‘e (people).

Unlike many of those who live on the continent, Hawai‘i people, whether we reside here or elsewhere, share a “homing” bond with these Islands. Many of us fondly recall American Idol winner Iam Tongi being asked where he was from and immediately responding, “Kahuku, O‘ahu.” When asked where he lived, he answered, “Seattle.”

Yet Hawai‘i may be the only state in the United States where residents don’t share a common moniker. The original inhabitants of these Islands and their descendants are contemporarily referred to as “Hawaiians.” Ironically, Hawaiian is an English word; ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i words do not end in consonants. Indigenous Hawai‘i people referred to themselves as kānaka maoli.

During the days of the Hawaiian Kingdom, all subjects were called Hawaiian, regardless of ancestry. Things changed after the U.S. occupied the Islands, especially during the middle territorial decades, when Hawai‘i residents, including kānaka maoli, were classified by their place of origin (i.e., Native Hawaiian).

In Hawai‘i, we are encouraged to be proud of who we are and where we came from. It’s one of the things that makes the Islands special. The 1970s began with students at the University of Hawai‘i revolting and demanding to be taught “their history, their way.” Today, books are published and classes are taught about the hardships faced and triumphs realized by Hawai‘i’s multiethnic population. I personally am very proud that, unlike when I attended school, children across the state are being taught Hawai‘i’s history, culture and ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i.

What makes Hawai‘i unique is that it offers each of us an opportunity to be more than our backstory. Hawai‘i begins that relationship by first stealing our heart. In 2016, a 10-year kapu (moratorium) called the “Try Wait” initiative was established that prohibits fishing and the harvesting of any marine life from the 3.6-mile coastline in front of the Hualālai Resort on Hawai‘i Island. Try Wait was a collaborative effort between the resort and kānaka lineal descendants of the area to restore the marine life that had been over-harvested in recent decades. While conservationists are looking forward to when people can view a natural aquarium of ocean life in front of the resort, Native Hawaiian kūpuna are anticipating when the sea will once again be a bountiful pantry.

Ingrained in Island life is the insight that if we mālama our ‘āina and kai, their bounty will feed us. Aloha ‘āina results in ‘āina aloha, which sustains life (aloha ola). It is this relationship that binds us to our Island home, and it is within this reciprocal relationship that Hawai‘i’s “soul” thrives.

SEE ALSO: Protecting Hawai‘i’s Soul

In January 1976, an armada filled with people started across the ocean from Maui to Kaho‘olawe to protest the bombing of the island. Before they could get there, a Coast Guard helicopter circled overhead and began copying the boat licenses. The captains, concerned that their boats would be confiscated, reluctantly turned back. Just when it looked like the invasion was over, a Boston whaler appeared over the waves driven by a tanned captain with sun-bleached hair, accompanied by another man and woman. All three individuals appeared to be haole in their late 20s.

The captain drove up and asked the remaining protesters if they needed a ride. He first took nine individuals (including George Helm, Walter Ritte, Emmett Aluli and Steve Morse) to Kaho‘olawe and then made a second trip, returning with supplies that were on the boats that had gone back. Thus, the historic “First Landing of the Kaho‘olawe Nine” occurred. Later, Morse would write that the young captain spoke with such an unmistakable local accent that you knew he “was either born and raised in Hawai‘i or had spent enough time around Hawaiians that he had become one.”

Helm taught that it didn’t matter who you were, that if you believed in the sanctity of Kaho‘olawe, you were part of an ‘ohana, the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana. The moment that the captain and his companions decided that stopping the bombing was more important than losing a boat, they were no longer strangers but family.

Today, we face tough, often emotional, issues. There are still injustices to right, a diaspora that is stealing our people, an economy that may be extracting more than it provides, and the list goes on. Furthermore, we don’t always agree or even always like each other. Rather than despair, we need to recognize that our strength is the love we share for our Island home. By focusing on aloha ‘āina, we create the space for all of us, despite our differences, to unify as one lāhui (community).

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter whether your ancestors came in canoes a thousand years ago or on cargo ships filled with laborers or in a jet plane, we who aloha Hawai‘i have the foundation to preserve it for future generations. This is our home because we choose to belong to this ‘āina. So, if anyone asks who you are, tell them with pride, “I am kō Hawai‘i.”

John Waihe‘e III served as the fourth governor of the state of Hawai‘i from 1986 to 1994. The Honoka‘a native, who was the first Native Hawaiian to serve in that capacity, is a core team member of the Rediscovering Hawai‘i’s Soul movement.